Trustworthy Smart Cities through Risk Management: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

In the Smart City context, the organization level may include entities such as the mayor’s office and key risk-related offices such as those of the chief risk officer, chief information officer, chief information security officer, or chief privacy officer. | In the Smart City context, the organization level may include entities such as the mayor’s office and key risk-related offices such as those of the chief risk officer, chief information officer, chief information security officer, or chief privacy officer. | ||

Underneath this level may be a transportation mission area or an acquisition management business process area. These areas would naturally involve a wider array of stakeholders; for example, the transportation mission area may include a wide variety of transportation-related agencies, including the departments of transportation and public works as well as emergency management and law | |||

enforcement entities. | |||

At the most tactical level – the information system level – the risk management process may focus on a single system, solution, or capability. Example systems of interest could be defined as a smart parking meter system or a system comprised of traffic sensors and the back-end traffic analytics capability. It should be noted that the depiction in the pyramid does not explicitly address the relationships with external organizations (e.g., county, state, private sector); however, supply chain risk management is certainly a critical part of the RMF. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|- | |||

|'''Cybersecurity and Privacy: Differences and Overlap ''' | |||

The risk management process can apply to both cybersecurity and privacy. Indeed, many privacy risks and the management of those risks can be viewed as identical to or synonymous with cybersecurity risks. However, there are instances when privacy may deviate from the traditional notion of cybersecurity. Nonetheless, cybersecurity and privacy are undoubtedly interrelated and complementary and coordination between those two areas of risk is necessary. | |||

Cybersecurity traditionally focuses on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data and data systems. Privacy generally pertains to specific types of data - such as personally identifiable information (PII), protected health information (PHI -It is important to note that there are varying definitions of privacy. While some definitions of privacy may be more focused on the individual citizen and associated personal data (e.g., PII, PHI), privacy principles can also pertain to intellectual property or other corporate or government data, for example. ) - and goes beyond the three core attributes of cybersecurity. Privacy necessarily requires cybersecurity (in particular confidentiality), but privacy also involves the protection of data over its entire lifecycle, including determining how it is created; how it is collected; how and where it is processed and stored; how it is used and by whom; how it is disseminated or disclosed; and how it is disposed. | |||

While there are often shared goals between cybersecurity and privacy, it is worth noting that cybersecurity and privacy could potentially conflict at times. For example, a cybersecurity capability may require the decryption of data, thereby creating the potential for exposure or misuse. At a broader level, cybersecurity is often associated with mass collection of data and surveillance, which can raise | |||

many privacy questions. There are certainly mitigations and controls to address such conflicts (e.g., technical and administrative controls, such as data de-identification and data minimization) but ultimately, coordination between the two disciplines is necessary to ensure desired cybersecurity, privacy, and shared outcomes are achieved. | |||

Cybersecurity and privacy provide a means for building and establishing trust in Smart City environments. The burden, however, is on the municipality or relevant Smart City capability providers to offer adequate levels of cybersecurity and privacy. The expectation cannot be on the individual or citizen to manage and control the cybersecurity and privacy of their own data within the Smart City environment. | |||

This document is intended to present cybersecurity and privacy risk management as a combined process. In the context of Smart Cities, cybersecurity and privacy cannot and should not be dis-aggregated. | |||

|} | |||

Existing Risk Management Guidelines, Standards, and References The NIST RMF is not a single standard or checklist that instructs how to perform risk management. Rather, the RMF is really a suggested approach to risk management and is supported by a collection of more detailed and specific guidelines that address specific aspects of risk management (e.g., selection of security and privacy controls). The RMF and any of the associated guidance can be used as the foundation for or as a supplement to new and existing organizational risk management processes. Furthermore, there is also a variety of risk management guidelines, standards, and references developed by organizations other than NIST that may be appropriate for some organizations. | |||

''Example U.S. Risk Management-Related Guidelines, Standards, and References'' | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|- | |||

!U.S. Publications | |||

!Title | |||

|- | |||

|NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-37 Rev. 2 | |||

|Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy | |||

|- | |||

|NIST SP 800-39 | |||

|Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View | |||

|- | |||

|Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 199 | |||

|Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-60 Rev. 1 | |||

|Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories | |||

|- | |||

|FIPS 200 | |||

|Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-53 Rev. 5 (Draft) | |||

|Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-128 | |||

|Guide for Security-Focused Configuration Management of Information Systems | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-34 Rev. 1 | |||

|Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-61 Rev. 2 | |||

|Computer Security Incident Handling Guide | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-53A Rev. 4 | |||

|Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Information Systems and Organizations: Building Effective Assessment Plans | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-137 | |||

|Information Security Continuous Monitoring (ISCM) for Federal Information Systems and Organizations | |||

|- | |||

|SP 800-161 | |||

|Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems and Organizations | |||

|- | |||

|NIST Internal Report (NISTIR) 8062 | |||

|An Introduction to Privacy Engineering and Risk Management in Federal Systems | |||

|- | |||

|NIST Cybersecurity Framework v1.1 | |||

|Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity | |||

|- | |||

|NISTIR 8170 (Draft) | |||

|The Cybersecurity Framework: Implementation Guidance for Federal Agencies | |||

|} | |||

Revision as of 19:44, December 19, 2021

| Cybersecurity and Privacy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sectors | Cybersecurity and Privacy |

| Contact | Lan Jenson |

| Topics | |

- Authors

[[File:|x100px|link=Alex Huppenthal]]

[[File:|x100px|link=Alex Huppenthal]]

[[File:|x100px|link=Ed Walker]]

[[File:|x100px|link=Ed Walker]]

{{{summary}}}

Organizations participating in the Smart City environment – whether as municipalities, critical infrastructure operators, product or service providers, or citizens – already consider at least some aspects of risk (e.g., business risk, reputational risk) in the development and deployment of Smart City capabilities and solutions. And one growing area of risk is cybersecurity and privacy risk.

Many of the cybersecurity- and privacy-related vulnerabilities and threats that could affect Smart City environments are similar to those commonly found in the traditional enterprise IT environment. The cyber-physical aspects of Smart Cities as well as the interconnections and interdependencies that are characteristic of Smart City solutions could potentially result in more complex and catastrophic consequences (e.g., disruption of government services to citizens; terrorist event; danger to public health or safety). The recognition of these vulnerabilities, threats, and consequences necessitates the consideration and adoption of risk management processes and practices that can help Smart City organizations make risk-based business decisions, such as identifying what levels of risk are acceptable and where investments need to be made to mitigate risk.

Cybersecurity and privacy risk management does not have to be an undue burden. In fact, there are a variety of tools that can make it easier to integrate risk management; and risk management, in turn, will be an enabler for Smart City solutions and capabilities.

- There is an abundance of existing guidelines, standards, and references to inform and improve risk management processes

- Risk management can be a tool and enabler for Smart City solutions by establishing and increasing trust in government and trust in systems *Leveraging existing relationships (e.g., inter-/intra-governmental, public-private partnerships, new and existing suppliers) to collaborate on risk management objectives can increase effectiveness and efficiency in a limited-resource

environment While the need for cybersecurity and privacy risk management is clear, a successful risk management program will require coordination and commitment from all levels of government and from all Smart City participants.

Organizations will need to adopt processes and practices that are appropriate for their specific needs. The NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF) is one tool, of many, that can help organizations supplement and refine existing risk management practices or establish new risk management processes. At the most generic level, the RMF consists of seven iterative steps - an initial preparatory step to ensure readiness to execute the process followed by the six main steps - that can be more strategic or tactical as needed.

0. Prepare for risk management at all organizational levels 1. Categorize information and information systems 2. Select and tailor security and privacy controls 3. Implement security and privacy controls 4. Assess (independently) security and privacy controls for proper and intended implementation, operation, and risk outcomes 5. Authorize system operation 6. Monitor (continuously) to adjust to system and environment changes and to maintain awareness of organization risk posture

Operationalizing, standardizing and coordinating risk management across an organization is critical for minimizing cybersecurity and privacy risks during the development and operation of Smart City solutions. Cities – and all other participants in the Smart City environment – must determine the appropriate policies and processes to adopt and implement based on their current risk management practices, risk posture, and their risk management strategy.

What is Cybersecurity and Privacy Risk Management?

Risk management is a critical practice that not only assists in mitigating potential catastrophic consequences but also enables the success of Smart City systems, projects, and programs by enhancing trust. The risk management process ultimately helps organizations make risk-based business decisions, such as identifying what levels of risk are acceptable to the organization and where investment needs to be made to mitigate risk, namely by reducing vulnerabilities (e.g., implementing security or privacy controls) or limiting consequences (e.g., developing continuity of operations capabilities, purchasing cyber insurance to minimize financial loss). That said, risk management is more substantial than simply implementing more cybersecurity and privacy controls. Organizations can make decisions and investments to reduce vulnerabilities and consequences. The third component of risk – threat – is external to the organization and typically cannot be directly controlled. However, organizations need to understand their sector, industry, or regional threat environment to inform their risk management processes and decisions.

NIST’s Approach to Organization-Wide Risk Management

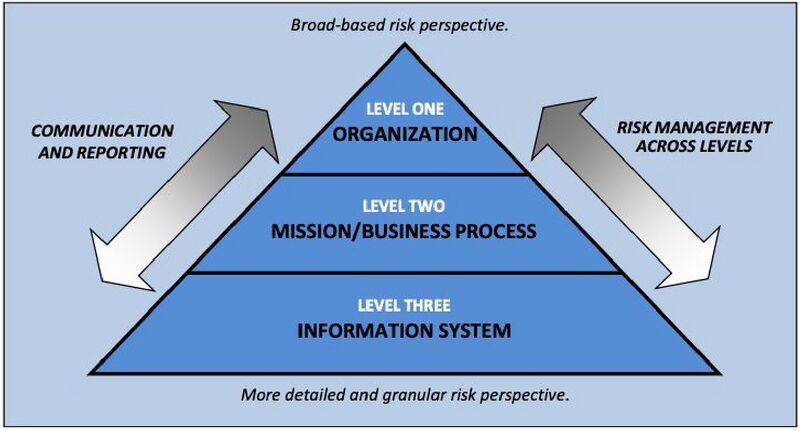

Risk management can be viewed as a process and practice that requires participation from, and engagement of, all levels of a given organization. The risk management functions at each level are interconnected and inform the risk decisions made at the other levels. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Risk Management Framework (RMF) proposes a three-level approach to risk management: (1) organization level; (2) mission/business process level; and (3) information system or system component level.

At the top of the pyramid, the organization establishes the risk management strategy, communicates risk management guidance, identifies missions and business processes, and provides oversight of the organization’s risk posture. The risk guidance developed at the strategic levels determines the risk management activities performed at the lower, tactical levels – e.g., the information system and system component level.

The security and privacy risk management practices ultimately implemented at the information system level directly reflect the risk management principles defined by the organization. Reporting of system risk posture up to the organization level is intended to provide an aggregate view of risk across the organization, allowing the organization to adjust and achieve the desired risk posture.

In the Smart City context, the organization level may include entities such as the mayor’s office and key risk-related offices such as those of the chief risk officer, chief information officer, chief information security officer, or chief privacy officer.

Underneath this level may be a transportation mission area or an acquisition management business process area. These areas would naturally involve a wider array of stakeholders; for example, the transportation mission area may include a wide variety of transportation-related agencies, including the departments of transportation and public works as well as emergency management and law enforcement entities.

At the most tactical level – the information system level – the risk management process may focus on a single system, solution, or capability. Example systems of interest could be defined as a smart parking meter system or a system comprised of traffic sensors and the back-end traffic analytics capability. It should be noted that the depiction in the pyramid does not explicitly address the relationships with external organizations (e.g., county, state, private sector); however, supply chain risk management is certainly a critical part of the RMF.

| Cybersecurity and Privacy: Differences and Overlap

The risk management process can apply to both cybersecurity and privacy. Indeed, many privacy risks and the management of those risks can be viewed as identical to or synonymous with cybersecurity risks. However, there are instances when privacy may deviate from the traditional notion of cybersecurity. Nonetheless, cybersecurity and privacy are undoubtedly interrelated and complementary and coordination between those two areas of risk is necessary. Cybersecurity traditionally focuses on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data and data systems. Privacy generally pertains to specific types of data - such as personally identifiable information (PII), protected health information (PHI -It is important to note that there are varying definitions of privacy. While some definitions of privacy may be more focused on the individual citizen and associated personal data (e.g., PII, PHI), privacy principles can also pertain to intellectual property or other corporate or government data, for example. ) - and goes beyond the three core attributes of cybersecurity. Privacy necessarily requires cybersecurity (in particular confidentiality), but privacy also involves the protection of data over its entire lifecycle, including determining how it is created; how it is collected; how and where it is processed and stored; how it is used and by whom; how it is disseminated or disclosed; and how it is disposed. While there are often shared goals between cybersecurity and privacy, it is worth noting that cybersecurity and privacy could potentially conflict at times. For example, a cybersecurity capability may require the decryption of data, thereby creating the potential for exposure or misuse. At a broader level, cybersecurity is often associated with mass collection of data and surveillance, which can raise many privacy questions. There are certainly mitigations and controls to address such conflicts (e.g., technical and administrative controls, such as data de-identification and data minimization) but ultimately, coordination between the two disciplines is necessary to ensure desired cybersecurity, privacy, and shared outcomes are achieved. Cybersecurity and privacy provide a means for building and establishing trust in Smart City environments. The burden, however, is on the municipality or relevant Smart City capability providers to offer adequate levels of cybersecurity and privacy. The expectation cannot be on the individual or citizen to manage and control the cybersecurity and privacy of their own data within the Smart City environment. This document is intended to present cybersecurity and privacy risk management as a combined process. In the context of Smart Cities, cybersecurity and privacy cannot and should not be dis-aggregated. |

Existing Risk Management Guidelines, Standards, and References The NIST RMF is not a single standard or checklist that instructs how to perform risk management. Rather, the RMF is really a suggested approach to risk management and is supported by a collection of more detailed and specific guidelines that address specific aspects of risk management (e.g., selection of security and privacy controls). The RMF and any of the associated guidance can be used as the foundation for or as a supplement to new and existing organizational risk management processes. Furthermore, there is also a variety of risk management guidelines, standards, and references developed by organizations other than NIST that may be appropriate for some organizations.

Example U.S. Risk Management-Related Guidelines, Standards, and References

| U.S. Publications | Title |

|---|---|

| NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-37 Rev. 2 | Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy |

| NIST SP 800-39 | Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View |

| Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 199 | Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems |

| SP 800-60 Rev. 1 | Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories |

| FIPS 200 | Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems |

| SP 800-53 Rev. 5 (Draft) | Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations |

| SP 800-128 | Guide for Security-Focused Configuration Management of Information Systems |

| SP 800-34 Rev. 1 | Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems |

| SP 800-61 Rev. 2 | Computer Security Incident Handling Guide |

| SP 800-53A Rev. 4 | Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Information Systems and Organizations: Building Effective Assessment Plans |

| SP 800-137 | Information Security Continuous Monitoring (ISCM) for Federal Information Systems and Organizations |

| SP 800-161 | Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems and Organizations |

| NIST Internal Report (NISTIR) 8062 | An Introduction to Privacy Engineering and Risk Management in Federal Systems |

| NIST Cybersecurity Framework v1.1 | Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity |

| NISTIR 8170 (Draft) | The Cybersecurity Framework: Implementation Guidance for Federal Agencies |