Trustworthy Smart Cities through Risk Management: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| blueprint = Cybersecurity and Privacy | | blueprint = Cybersecurity and Privacy | ||

| sectors = Cybersecurity and Privacy | | sectors = Cybersecurity and Privacy | ||

| authors = Lan Jenson, David Balenson, Adnan Baykal, Gary Dennis, Wayne Dennis | | authors = Lan Jenson, David Balenson, Adnan Baykal, Gary Dennis, Wayne Dennis, Damon Kachur, Benny Lee, Carmen Marsh, Aleta Nye, Carmen Parada, Renil Paramel, Bill Pugh, Maryam Rahmani, Carter Schoenberg, Sushmita Senmajumdar, Deborah Shands, Dean Skidmore, Scott Tousley, Edward Walker, Ruwan Welaratna, Paul Wertz, Peter Wong | ||

| poc = Lan Jenson | | poc = Lan Jenson | ||

| email = lan@cybertrustamerica.org | | email = lan@cybertrustamerica.org | ||

Revision as of 03:19, January 11, 2022

| Cybersecurity and Privacy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sectors | Cybersecurity and Privacy |

| Contact | Lan Jenson |

| Topics | |

- Authors

{{{summary}}}

Organizations participating in the Smart City environment – whether as municipalities, critical infrastructure operators, product or service providers, or citizens – already consider at least some aspects of risk (e.g., business risk, reputational risk) in the development and deployment of Smart City capabilities and solutions. And one growing area of risk is cybersecurity and privacy risk.

Many of the cybersecurity- and privacy-related vulnerabilities and threats that could affect Smart City environments are similar to those commonly found in the traditional enterprise IT environment. The cyber-physical aspects of Smart Cities as well as the interconnections and interdependencies that are characteristic of Smart City solutions could potentially result in more complex and catastrophic consequences (e.g., disruption of government services to citizens; terrorist event; danger to public health or safety). The recognition of these vulnerabilities, threats, and consequences necessitates the consideration and adoption of risk management processes and practices that can help Smart City organizations make risk-based business decisions, such as identifying what levels of risk are acceptable and where investments need to be made to mitigate risk.

Cybersecurity and privacy risk management does not have to be an undue burden. In fact, there are a variety of tools that can make it easier to integrate risk management; and risk management, in turn, will be an enabler for Smart City solutions and capabilities.

- There is an abundance of existing guidelines, standards, and references to inform and improve risk management processes

- Risk management can be a tool and enabler for Smart City solutions by establishing and increasing trust in government and trust in systems *Leveraging existing relationships (e.g., inter-/intra-governmental, public-private partnerships, new and existing suppliers) to collaborate on risk management objectives can increase effectiveness and efficiency in a limited-resource

environment While the need for cybersecurity and privacy risk management is clear, a successful risk management program will require coordination and commitment from all levels of government and from all Smart City participants.

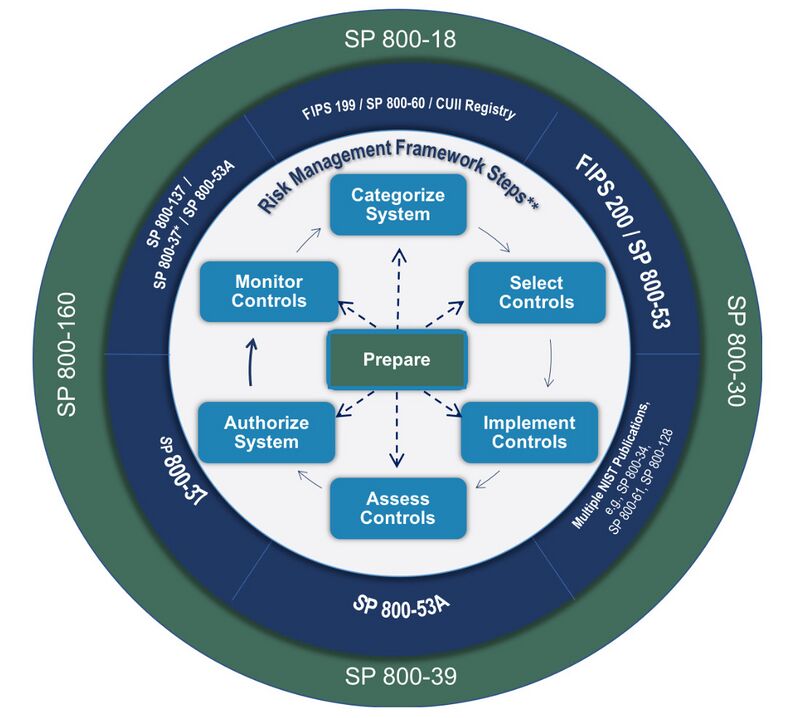

Organizations will need to adopt processes and practices that are appropriate for their specific needs. The NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF) is one tool, of many, that can help organizations supplement and refine existing risk management practices or establish new risk management processes. At the most generic level, the RMF consists of seven iterative steps - an initial preparatory step to ensure readiness to execute the process followed by the six main steps - that can be more strategic or tactical as needed.

0. Prepare for risk management at all organizational levels 1. Categorize information and information systems 2. Select and tailor security and privacy controls 3. Implement security and privacy controls 4. Assess (independently) security and privacy controls for proper and intended implementation, operation, and risk outcomes 5. Authorize system operation 6. Monitor (continuously) to adjust to system and environment changes and to maintain awareness of organization risk posture

Operationalizing, standardizing and coordinating risk management across an organization is critical for minimizing cybersecurity and privacy risks during the development and operation of Smart City solutions. Cities – and all other participants in the Smart City environment – must determine the appropriate policies and processes to adopt and implement based on their current risk management practices, risk posture, and their risk management strategy.

What is Cybersecurity and Privacy Risk Management?

Risk management is a critical practice that not only assists in mitigating potential catastrophic consequences but also enables the success of Smart City systems, projects, and programs by enhancing trust. The risk management process ultimately helps organizations make risk-based business decisions, such as identifying what levels of risk are acceptable to the organization and where investment needs to be made to mitigate risk, namely by reducing vulnerabilities (e.g., implementing security or privacy controls) or limiting consequences (e.g., developing continuity of operations capabilities, purchasing cyber insurance to minimize financial loss). That said, risk management is more substantial than simply implementing more cybersecurity and privacy controls. Organizations can make decisions and investments to reduce vulnerabilities and consequences. The third component of risk – threat – is external to the organization and typically cannot be directly controlled. However, organizations need to understand their sector, industry, or regional threat environment to inform their risk management processes and decisions.

NIST’s Approach to Organization-Wide Risk Management

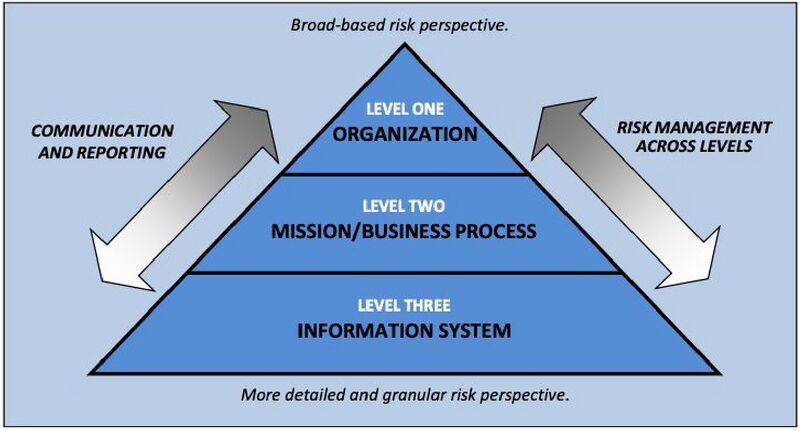

Risk management can be viewed as a process and practice that requires participation from, and engagement of, all levels of a given organization. The risk management functions at each level are interconnected and inform the risk decisions made at the other levels. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Risk Management Framework (RMF) proposes a three-level approach to risk management: (1) organization level; (2) mission/business process level; and (3) information system or system component level.

At the top of the pyramid, the organization establishes the risk management strategy, communicates risk management guidance, identifies missions and business processes, and provides oversight of the organization’s risk posture. The risk guidance developed at the strategic levels determines the risk management activities performed at the lower, tactical levels – e.g., the information system and system component level.

The security and privacy risk management practices ultimately implemented at the information system level directly reflect the risk management principles defined by the organization. Reporting of system risk posture up to the organization level is intended to provide an aggregate view of risk across the organization, allowing the organization to adjust and achieve the desired risk posture.

In the Smart City context, the organization level may include entities such as the mayor’s office and key risk-related offices such as those of the chief risk officer, chief information officer, chief information security officer, or chief privacy officer.

Underneath this level may be a transportation mission area or an acquisition management business process area. These areas would naturally involve a wider array of stakeholders; for example, the transportation mission area may include a wide variety of transportation-related agencies, including the departments of transportation and public works as well as emergency management and law enforcement entities.

At the most tactical level – the information system level – the risk management process may focus on a single system, solution, or capability. Example systems of interest could be defined as a smart parking meter system or a system comprised of traffic sensors and the back-end traffic analytics capability. It should be noted that the depiction in the pyramid does not explicitly address the relationships with external organizations (e.g., county, state, private sector); however, supply chain risk management is certainly a critical part of the RMF.

| Cybersecurity and Privacy: Differences and Overlap

The risk management process can apply to both cybersecurity and privacy. Indeed, many privacy risks and the management of those risks can be viewed as identical to or synonymous with cybersecurity risks. However, there are instances when privacy may deviate from the traditional notion of cybersecurity. Nonetheless, cybersecurity and privacy are undoubtedly interrelated and complementary and coordination between those two areas of risk is necessary. Cybersecurity traditionally focuses on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data and data systems. Privacy generally pertains to specific types of data - such as personally identifiable information (PII), protected health information (PHI -It is important to note that there are varying definitions of privacy. While some definitions of privacy may be more focused on the individual citizen and associated personal data (e.g., PII, PHI), privacy principles can also pertain to intellectual property or other corporate or government data, for example. ) - and goes beyond the three core attributes of cybersecurity. Privacy necessarily requires cybersecurity (in particular confidentiality), but privacy also involves the protection of data over its entire lifecycle, including determining how it is created; how it is collected; how and where it is processed and stored; how it is used and by whom; how it is disseminated or disclosed; and how it is disposed. While there are often shared goals between cybersecurity and privacy, it is worth noting that cybersecurity and privacy could potentially conflict at times. For example, a cybersecurity capability may require the decryption of data, thereby creating the potential for exposure or misuse. At a broader level, cybersecurity is often associated with mass collection of data and surveillance, which can raise many privacy questions. There are certainly mitigations and controls to address such conflicts (e.g., technical and administrative controls, such as data de-identification and data minimization) but ultimately, coordination between the two disciplines is necessary to ensure desired cybersecurity, privacy, and shared outcomes are achieved. Cybersecurity and privacy provide a means for building and establishing trust in Smart City environments. The burden, however, is on the municipality or relevant Smart City capability providers to offer adequate levels of cybersecurity and privacy. The expectation cannot be on the individual or citizen to manage and control the cybersecurity and privacy of their own data within the Smart City environment. This document is intended to present cybersecurity and privacy risk management as a combined process. In the context of Smart Cities, cybersecurity and privacy cannot and should not be dis-aggregated. |

Existing Risk Management Guidelines, Standards, and References The NIST RMF is not a single standard or checklist that instructs how to perform risk management. Rather, the RMF is really a suggested approach to risk management and is supported by a collection of more detailed and specific guidelines that address specific aspects of risk management (e.g., selection of security and privacy controls). The RMF and any of the associated guidance can be used as the foundation for or as a supplement to new and existing organizational risk management processes. Furthermore, there is also a variety of risk management guidelines, standards, and references developed by organizations other than NIST that may be appropriate for some organizations.

Example U.S. Risk Management-Related Guidelines, Standards, and References

| U.S. Publications | Title |

|---|---|

| NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-37 Rev. 2 | Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy |

| NIST SP 800-39 | Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View |

| Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 199 | Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems |

| SP 800-60 Rev. 1 | Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories |

| FIPS 200 | Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems |

| SP 800-53 Rev. 5 (Draft) | Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations |

| SP 800-128 | Guide for Security-Focused Configuration Management of Information Systems |

| SP 800-34 Rev. 1 | Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems |

| SP 800-61 Rev. 2 | Computer Security Incident Handling Guide |

| SP 800-53A Rev. 4 | Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Information Systems and Organizations: Building Effective Assessment Plans |

| SP 800-137 | Information Security Continuous Monitoring (ISCM) for Federal Information Systems and Organizations |

| SP 800-161 | Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems and Organizations |

| NIST Internal Report (NISTIR) 8062 | An Introduction to Privacy Engineering and Risk Management in Federal Systems |

| NIST Cybersecurity Framework v1.1 | Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity |

| NISTIR 8170 (Draft) | The Cybersecurity Framework: Implementation Guidance for Federal Agencies |

Example International Risk Management-Related Guidelines, Standards, and References

| International Publications | Title |

|---|---|

| ISO 31000:2018 | Risk Management – Guidelines |

| ISO/IEC 27000 | Information Security Management Systems (ISMS) Standards |

| Institute of Risk Management (IRM)/The Public Risk Management Association (Alarm)/The Association of Insurance and Risk Managers (AIRMIC) 2002 | Risk Management Standard |

| Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) 2004 | Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework |

| OCEG Red Book | Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) Capability Model |

| ISACA COBIT 5 | A Business Framework for the Governance and Management of Enterprise IT |

Given the information/data- and technology-centric nature of Smart Cities, the remainder of this risk management section focuses on the NIST RMF as a starting point for addressing Smart City cybersecurity and privacy risk management. While this summary of the NIST RMF is not intended to be prescriptive, the RMF (as well as the other existing documents) can be used as a tool to inform new risk management practices and to supplement existing risk management processes. Ultimately, organizations will have to determine which practices to implement and what the appropriate references and guidelines for those practices are.

| Relationship Between the Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) and the Risk Management Framework (RMF)

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) has received a lot of attention in the last several years as a voluntary and flexible framework for critical infrastructure organizations to improve their cybersecurity risk management practices. It is meant to be complementary to existing risk management and information security programs, and help strengthen them. The processes and taxonomies (e.g., functions, categories, subcategories) presented by CSF can generate inputs for the RMF (e.g., establishing and standardizing cybersecurity requirements, establishing tailored control baselines, or developing baseline and target profiles) and also facilitate the communication and reporting of cybersecurity and privacy risk information across the organization. The bulk of the direct alignment between the CSF and the RMF is in the RMF “Prepare” step, which is further discussed later in this document. The alignment between CSF and the other RMF steps varies considerably and can be dependent on the framework user’s interpretation. The latest version of the RMF (SP 800-37 Rev. 2) was explicitly updated to provide references that indicate the alignment between the CSF and specific RMF steps and tasks. |

| NIST Cybersecurity Framework Core | ||

|---|---|---|

| Function | Description | Categories |

| Identify | Develop understanding of systems, people, assets, data, and capabilities. | Asset Management; Business Environment; Governance; Risk Assessment; Risk Management Strategy; and Supply Chain Risk |

| Protect | Develop and implement appropriate safeguards to ensure delivery of critical services | Identity Management and Access Control; Awareness and Training; Data Security; Information Protection Processes and Procedures; Maintenance; and Protective Technologies |

| Detect | Develop and implement appropriate activities to identify the occurrence of a cybersecurity event | Anomalies and Events; Security Continuous Monitoring; and Detection Processes |

| Respond | Develop and implement appropriate activities to take action regarding a detected cybersecurity incident | Response Planning; Communications; Analysis; Mitigation; and Improvements |

| Recover | Develop and implement appropriate activities to maintain resilience and restore any capabilities and services | Recovery Planning; Improvements; and Communications |

NIST Risk Management Framework

The latest version of the NIST RMF (Revision 2) describes a seven-step risk management process where the original six steps are preceded by a foundational preparation phase (i.e., Prepare). This process as a whole, as well as each step in the process, is iterative in nature and is continuously applied to information systems and information flows across the organization. Risk management should be performed in this continuous manner to account for changes in organization risk management strategy, evolution of the threat landscape, adoption of new technology, and other anticipated and unanticipated developments.

NIST Risk Management Framework Diagram and Corresponding NIST Guidance

Step 0: Prepare

Organizational preparation is essential to attaining the risk reduction benefits of following the steps in the NIST RMF. The preparation step focuses on necessary communication and consensus-building among organizational leaders. Identifying high-impact and/or high-value systems, reaching consensus on protection and privacy priorities, risk tolerance, and allocating resources to implement and monitor controls are key issues to be addressed in preparation for executing the remaining steps in the RMF in a cost-effective and consistent manner.

Preparation is also necessary at the lower, tactical levels – i.e., system level. These activities are similar in nature and scope to the organizational preparation tasks. This includes identifying key system stakeholders, identifying and prioritizing assets and information types, and in general, determining the risk management status quo (i.e., the current state of risk management practices and posture) and intended risk objectives for the system of interest.

Key Organizational/Strategic “Prepare” Tasks and Steps

- Identify and assign key risk management roles and responsibilities' See NIST Special Publication 800-37 Rev. 2, “Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: Appendix D” for descriptions of example roles and responsibilities that may be important for a risk management process.

- Establish and communicate organization risk management strategy

- Conduct or update organization-wide risk assessment, Reference Appendix A and B for an example of a risk assessment process and template. Another example of a risk assessment tool is the Center for Internet Security’s (CIS) Nationwide Cybersecurity Review (NCSR)

- Determine and communicate organization-wide control baselines, More detail on control baselines can be found in Step 2: Select.

- Identify and document common controls, More detail on common controls can be found in Step 2: Select.

- Prioritize information systems, More detail on prioritizing information systems can be found in Step 1: Categorize.

- Develop, communicate, and implement organization continuous monitoring strategy

Step 1: Categorize

The security categorization step of the NIST RMF is critical for informing the subsequent steps of the RMF process. The primary focus is for organizations and system owners to determine the potential consequences (e.g., mission, legal, continuity of operations) associated with each information type (e.g., personally identifiable information (PII), accounting data, traffic information, energy production data) processed, stored, or transmitted by an information system in a systematic and consistent manner across the organization. This provides a structured process for prioritizing assets.

For each system, information types will need to be identified and categorized. The information types can be categorized based on potential impact values (i.e., low, moderate, high) for each security objective (i.e., confidentiality, integrity, availability). For example, the confidentiality impact value of PII is generally considered to be moderate by NIST. The figure below depicts NIST’s approach, which results in each information type being assigned one of nine possible “security objective-potential impact” combinations.

FIPS 199 Potential Impact Definitions for Security Objectives

| NIST Cybersecurity Framework Core | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Security Objective | Low | Moderate | High |

| Confidentiality

Preserving authorized restrictions on information access and disclosure, including means for protecting personal privacy and proprietary information. [44 U.S.C., SEC. 3542] |

The unauthorized disclosure of information could be expected to have a limited adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. | The unauthorized disclosure of information could be expected to have a serious adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. | The unauthorized disclosure of information could be expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. |

| Integrity

Guarding against improper information modification or destruction, and includes ensuring information non-repudiation and authenticity. [44 U.S.C., SEC. 3542] |

The unauthorized modification or destruction of information could be expected to have a limited adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. | The unauthorized modification or destruction of information could be expected to have a serious adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. | The unauthorized modification or destruction of information could be expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. |

| Availability

Availability Ensuring timely and reliable access to and use of information. [44 U.S.C., SEC. 3542] |

The disruption of access to or use of information or an information system could be expected to have a limited adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. | The disruption of access to or use of information or an information system could be expected to have a serious adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. | The disruption of access to or use of information or an information system could be expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. |

The highest potential impact identified for a given system can then be used to determine the security impact level of the information system as a whole (e.g., a system that processes a high-impact information type should be categorized as a high-impact information system). The system security category can prescribe, at a minimum, a predetermined security control baseline (e.g., baseline for high-impact information systems). Adjustments to information type impact values and system security categories may be necessary to account for specific risk considerations that are not evident in standard organizational guidance and security control baselines.

Key “Categorize” Tasks and Steps

- Prepare for system categorization, Note that there is some overlap between these “Categorize” steps and the system-level steps delineated in the “Prepare” phase.

- Identify information types

- Select the provisional impact values for each type of information

- Adjust the information type’s provisional impact values and system security category based on organization risk management strategy and guidance

- Determine, approve, and maintain the system security impact level (e.g., low/moderate/high)

A more detailed and succinct description and resource for this step of the RMF is available in the form of a Quick Start Guide on the NIST website.

Step 2: Select The selection of security controls – including, but not limited to, management, (Refer to Appendix A. Smart Cities Use Cases for more detailed examples of selection and implementation of specific security and privacy controls.) operational, and technical risk mitigations – is essential for protecting an organization’s systems and information and enables the execution of the organizational mission. Selection of security controls involves identifying the set of controls that can appropriately and adequately mitigate risk in a cost effective manner while also maintaining compliance with any applicable policies, standards, laws, or regulations. The security categorization process determines the set of baseline security controls from which the selection process begins (e.g., high-impact systems start with the high-impact baseline). The standardization of sets of baseline security controls can also enable organizations to convey security requirements to external vendors and service providers. Organizations and information system owners will need to make adjustments to the security controls to account for considerations such as organization-specific requirements; operating environment needs; targeted threats; and legal and regulatory compliance standards.

It is also important to note that there are three types of security controls that differ based on their scope and applicability: system-specific; common; and hybrid.

- System-specific: security capability for a specific information system

- Common: security capabilities for multiple information systems (or organization-wide)

- Hybrid: security capabilities that have both system-specific and common attributes

Taking a holistic view of an organization’s information systems, their security categories, and the organization’s risk profile can enable organizations to select a set of common controls to protect multiple information systems. This practice can prove to be more cost effective and can result in more consistency in technology, architecture, and process across the organization.

Key “Select” Tasks and Steps

- Choose a set of baseline security controls

- Tailor and supplement the baseline security controls to meet organization-, environment-, and system-specific needs

- Specify minimum assurance requirements, as necessary, to determine proper implementation and efficacy of security and privacy controls

- Complete system security and privacy plans

- Develop continuous monitoring strategy

- Review and approve system security and privacy plans

There is a multitude of existing reference material for selecting security and privacy controls and for establishing baseline sets of controls. The following are examples of existing resources:

- NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5 – Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations

- Center for Internet Security (CIS) [“Top 20”] Controls V7.1 and the CIS Controls Internet of Things Companion Guide

- NIST SP 800-66 Rev. 1 – An Introductory Resource Guide for Implementing the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule (This guidance can help organizations subject to HIPAA map NIST SP 800-53 security controls to HIPAA rule requirements.)

- NIST Cybersecurity Framework v1.1 - Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity

- NISTIR 8170 – The Cybersecurity Framework: Implementation Guidance for Federal Agencies and supplemental materials

- ISO/IEC 27002:2013 – Code of Practice for Information Security Controls

- CTIA Cybersecurity Certification Test Plan for IoT Devices, August 2018 Establishing and communicating the security and privacy control baselines is an important task in the “Prepare” phase of the RMF, and these baselines will need to be updated and re-disseminated to reflect changes in the risk and technology environment.

A more detailed and succinct description and resource for this step of the RMF is available in the form of a Quick Start Guide on the NIST website.

Step 3: Implement

Conceptually, the implement step of the RMF may be the most straightforward. The focus of this step is to implement the controls specified in the select step and to document the baseline configurations of these security controls. In circumstances where organizations or system owners may not be able to directly affect the implementation of a control – for example, in an external system or a specific COTS component – it may be necessary to test, evaluate, and validate prior to implementation to ascertain the presence and efficacy of an embedded security control.

Key “Implement” Tasks and Steps

- Implement controls specified in approved system security and privacy plans

- Establish baseline configurations for security and privacy controls

- Update system security and privacy plans to reflect control implementation outcomes

Step 4: Assess

The assessment step of the RMF focuses on assuring that implemented security controls – including system-specific, common, and hybrid – are implemented in a correct manner; operating as intended; and producing the intended security, privacy, or risk mitigation outcome. This generally requires identifying an experienced assessor or assessor team with the appropriate levels of technical and policy expertise as well as independence from the organization and system owners. This step – similar to the other steps and the entire RMF process – must be iterated as systems mature and as the organization’s risk posture evolves.

Key “Assess” Tasks and Steps

- Select independent assessor or assessor team

- Develop assessment plan

- Conduct security and privacy control assessment

- Report findings and recommendations

- Implement initial remediation actions, reassess remediated controls, and update system security and privacy plans

- Develop a plan of action and milestones (POA&M) for remediation of remaining deficiencies

Step 5: Authorize

The authorize step of the RMF evaluates whether the level of cybersecurity and privacy risk of operating an information system is acceptable to the organization and the mission. This determination takes into account the outputs from the previous steps of the RMF process, including system security and privacy plans; the system-specific, common, and hybrid controls specified therein; and the findings from the assessment step (i.e., step 4). The authorization decision is typically made by a senior management official internal to the organization. This authorizing official, in collaboration with other security, privacy, and risk personnel, takes the available information (e.g., system security and privacy plans, assessment reports, organizational risk management strategy) to analyze and determine the amount of risk associated with operating a given system. This step ultimately determines whether systems are authorized to operate or not authorized to operate, along with the associated terms and conditions (e.g., authorization duration).

Key “Authorize” Tasks and Steps

- Generate authorization package, including outputs from previous steps such as system security and privacy plans, supply chain risk management plans, security and privacy assessment reports, and POA&Ms

- Conduct risk analysis and risk determination (by authorizing official)

- Provide risk response (e.g., risk acceptance, risk mitigation)

- Approve or deny system authorization

- Report authorization to the organization for purposes of aggregated organization-wide security and privacy risk awareness

Step 6: Monitor

Continuous monitoring enables organizations to conduct the risk management process in a continuous, near real-time manner rather than as a rigid process with a pre-determined schedule. Changes in system configurations, hardware, software, interdependent systems and connections, threat environment, etc. are inevitable over the life of the system. As such changes occur, organizations need to be able to continuously evaluate system-specific and organizational risk posture and to adjust accordingly (e.g., re-categorize systems, select and implement additional controls, remove obsolete controls). While system owners may initially need to designate a frequency at which these monitoring tasks are performed, the objective is to continually mature to a more frequent, more continuous risk management process, especially for prioritized and high-impact systems and controls. For example, common controls may be of higher priority to be continuously monitored due to their broad application across enterprise information systems. The transition from periodic monitoring to more continuous monitoring can also be facilitated through the use of automated tools.

Key Organizational/Strategic “Monitor” Tasks and Steps

- Monitor system and environment changes

- Conduct ongoing assessment of security and privacy control effectiveness and ongoing risk analysis and response

- Update authorization status and related documents

- Report security and privacy posture

- Conduct ongoing system authorizations

- Dispose of systems, as necessary (i.e., when systems are removed from operation)

Key System-/Tactical-Level “Monitor” Tasks and Steps

- Prepare and develop a continuous monitoring plan

- Document changes to system or environment and determine potential impact

- Assess a subset of security and privacy controls

- Conduct remediation activities

- Update selected security and privacy controls and related documentation

- Report security status to organization

- Conduct risk analysis and determination

- Implement decommissioning plan, as necessary

A more detailed and succinct description and resource for this step of the RMF is available in the form of a Quick Start Guide on the NIST website.