Funding Models: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

==The General Fund Model== | ==The General Fund Model== | ||

{|class="wikitable" style="width: | {|class="wikitable" style="float:right;width:400px" | ||

!MINI CASE STUDY: SMCPUBLIC | !MINI CASE STUDY: SMCPUBLIC | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

=Conclusion= | =Conclusion= | ||

{|class="wikitable" style="float:right;width:400px" | |||

|Public Wi-Fi is now in a renaissance where new PPP models have been implemented, such as LinkNYC, while other agencies are successfully justifying expenditures from their general fund. | |||

|} | |||

Public Wi-Fi is now in a renaissance where new models and innovations have been implemented, such | Public Wi-Fi is now in a renaissance where new models and innovations have been implemented, such | ||

as LinkNYC, which are changing the perception of public-private Wi-Fi projects. Meanwhile, | as LinkNYC, which are changing the perception of public-private Wi-Fi projects. Meanwhile, | ||

| Line 189: | Line 193: | ||

or wrong answer to the funding model puzzle''' and neither model should be viewed as | or wrong answer to the funding model puzzle''' and neither model should be viewed as | ||

fundamentally superior to the other. | fundamentally superior to the other. | ||

Which direction a municipality takes depends largely on local factors, such as the regional ecosystem, the size of the municipality, the location and density (rural/suburban/urban), the economics, and the public-private partnership (PPP) opportunities that are available. As a result, each Muni Wi-Fi project will look slightly different and no two will be identical. | Which direction a municipality takes depends largely on local factors, such as the regional ecosystem, the size of the municipality, the location and density (rural/suburban/urban), the economics, and the public-private partnership (PPP) opportunities that are available. As a result, each Muni Wi-Fi project will look slightly different and no two will be identical. | ||

Revision as of 19:57, January 6, 2022

| Wireless | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sectors | Wireless | |||||

| Contact | David Witkowski | |||||

| Topics |

| |||||

Activities

| ||||||

- Authors

{{{summary}}}

Business Model

The Fundamental Question

Three primary business models clearly emerge for today’s Public Wi-Fi projects. The direction a municipality takes depends on a multitude of factors, many specific to the municipality itself, such as: the local economy, physical location, density and size of the municipality, private partners available, organizational structure, fiscal and financial situation, economic forecast, political landscape and, of course, the underlying philosophy and values of the community itself. These all play a critical role in the decision of how to fund a Public Wi-Fi project.

Thus, consider this the fundamental question: will the Wi-Fi system be a part of a public-private partnership (where the private firm absorbs some or all of the costs), a revenue generator (where some mechanism generates revenue to offset the cost to the agency), or, simply, a general fund initiative (i.e., a “public service”)? Questions to ask, include will the municipality use the network for human or machine connectivity and/or to create efficiencies or reduce expenses? This direction will answer the all- important question of sustainability (i.e., how will the Wi-Fi system be paid for and maintained over time?) It will also inform subsequent decisions down the line, such as whom to partner with and what types of investments will need to be made.

The Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Model

“PPP Model” is used here as a blanket umbrella for any model where a public agency partners with a private entity to deploy a Public Wi-Fi system. In many cases, agencies trade access to their assets (e.g., street poles, infrastructure in the public right-of-way, etc.) in exchange for having a Public Wi-Fi system deployed by the private firm.

PPP models have been around for a long time and there are myriad strategies that have been proposed over the years. In fact, the roots can be traced back to the Muni Wi-Fi 1.0 days and projects such as San Francisco’s EarthLink deal. While today’s models have had much more success, the underlying tenets remain the same: cities can benefit from having Public Wi-Fi deployed throughout their community, while avoiding, ether partially or, the up-front capital cost of construction and ongoing cost of maintenance. The cost comes in the form of an opportunity cost of the asset exchanged in the PPP structure.

Some recent projects that have been announced that fall under this model include:

- A recent partnership between the City of Sacramento, CA and Verizon. Sacramento exchanged access to over 100 city-owned poles and miles of its fiber conduit in exchange for free, Public Wi-Fi kiosks in 25+ public parks in the city. Verizon is expected to invest over US$100 million in the city over the next several years.

- Kansas City, MO launched Public Wi-Fi in 2016 through a strategic public-private partnership between the city, Cisco Systems, and Sprint. The city paid for US$3.7 million of the total US$16 million cost with Sprint and Cisco picking up the rest.

Considerations for Public-Private Partnerships

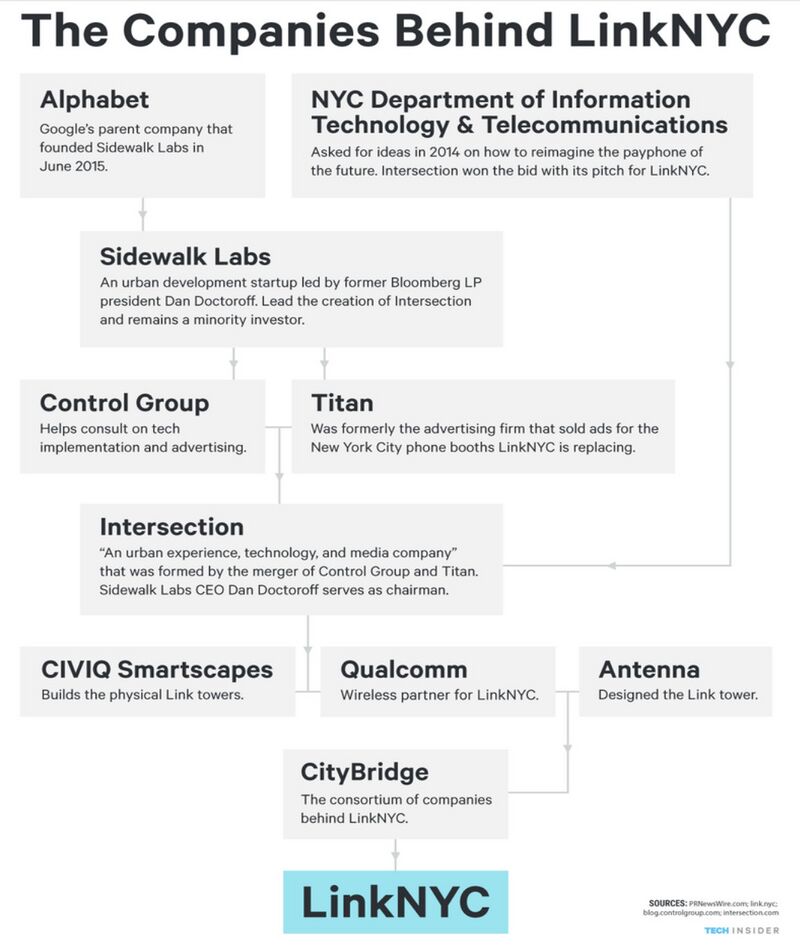

| MINI CASE STUDY: LINKNYC |

|---|

| The project that has received the most attention is arguably New York City’s “LinkNYC.” LinkNYC spawned from a competition New York City held in 2014 to replace its existing payphones with Wi-Fi hotspots. The innovation is to deliver large kiosk towers that display advertisements, way-finding, and act as Wi-Fi hotspots. Many partners, including Alphabet (Google), Intersection, CIVIA, Qualcomm, Antenna, and others came together under a consortium called “CityBridge” (see Figure 1). This team promises to deliver over 7,000 kiosks in New York City over the next 12 years, delivering free, gigabit speed Wi-Fi throughout all five boroughs. The system will return US$500 million in advertising revenue to the city over 10 years. It will cost US$200 million to build, with no cost to New York City. 1

The model is now operational in New York City and CIVIQ, one of the consortium partners who are responsible for building and installing the physical kiosk towers (a/k/a “Links”) has since announced similar deals with Miami-Dade County and Chicago to deploy Public Wi-Fi with zero cost to the municipalities. |

Public-private partnerships are attractive because they can deliver tremendous value for communities with little cost to municipalities themselves. However, there are still important considerations for those exploring a private- sector partnership. G.W.E.B. van Herpen, in an essay for the Dutch Ministry of Transport 15 , outlined some:

- Insecurity: Whenever two or more parties enter into a contract, there is a risk that the administrative efforts on each side will be frustrated by a lack of cooperation on the part of the other party(s).

- Inefficiencies: Due to a lack of contestability and competition.

- Culture gap: The private sector’s motive to take part in a public private partnership is generally profit-making or image-building; the public sector’s motive is merely social attractiveness …To overcome the gap in culture, trust is one of the most important aspects in a partnership; without trust, real success is hard to realize.

In sum, private partners have much different incentives, goals, timelines, operations, and cultures than public sector organizations. As such, not all public-private partnerships are created equal and public sector organizations should think carefully about the partners they select.

Some have called this the “Let Google Do It” approach arguing that private partners have developed deep skills- sets in Wi-Fi solutions and management and so municipalities should partner and not try to compete with them. It’s a persuasive point. However, one important See Chapter Appendix for a graphic piece in a public-private partnership is the contingency plan. What happens if the partnership or the private entity fails? The answer is not always clear, but it’s a question that needs to be answered in the beginning.

The Revenue Model

This Revenue Model is one where the agency deploying Public Wi-Fi uses some form of revenue generation to offset the cost of the building and maintaining the system. The revenue could be direct, such as charging users for on-demand or premium levels of service (i.e., faster speeds), or could be indirect, such as selling advertisements and/or usage data and statistics to advertising partners, while providing the service free of charge for the public. There are not many successful examples of publicly funded Wi-Fi systems (i.e., paid for with tax monies) that employ the Revenue Model. In many cases, it seems end-users are unwilling to pay for premium service if free service is available.

Meanwhile, there are emerging examples of successful advertising revenue from Public Wi-Fi systems, but in the cases where this is working these are actually PPP models where the private sector firm is responsible for building, managing and delivering the advertising platform, securing the relationships with the advertisers, and developing privacy policies for user data. In these cases, the private sector firms simply agree to cut the public-sector partner a check with some percentage of the revenue generated.

The General Fund Model

| MINI CASE STUDY: SMCPUBLIC |

|---|

| In 2012, voters in the County of San Mateo passed a half cent sales tax measure. Revenues from this tax increase have gone to fund Wi-Fi projects throughout the county, which ranges from dense, urban city to rural, forested and coastal areas. As of June, 2017, over 30 sites have been brought online to “SMC Public Wi-Fi” with more sites planned in the future. 1 |

On the other side of the coin is what, for this blueprint, we call the “General Fund” model. This is an umbrella term for any model for which the municipality itself pays for Wi-Fi through a funding source such as the general fund. In projects like this, the procurement is much more traditional with a selected vendor and negotiated contract vehicle. Most often, there is no expectation of generating revenue with these types of deployments. In addition, they are often installed and/or operated with the involvement of city staff. Sometimes, private-sector partnerships arise in this model, usually in the form of integrators or private partners who trade some for on services, such as assistance with the design, installation, operation, and/or maintenance of Wi-Fi systems for city assets of some form. However, at the end of the day, the municipality generally still writes a check for such services, so these forms of partnerships tend to resemble much more of a traditional vendor/customer paradigm.

When municipalities self-fund Public Wi-Fi initiatives, especially when the source is from existing monies, such as general fund or reserves, the projects tend to be on a smaller scale. This is simply a matter of cost: because the funding is much more limited, the projects cover a smaller area and require lower construction costs. Many cities start with their downtowns and other core areas, such as tourist attractions and retail/restaurant districts where Wi-Fi will provide the most “bang for the buck.”

However, municipalities are not limited to existing funds. They can raise new revenues through taxes, bonds, municipal loans, and the like.

Considerations for General Fund Model

When municipalities procure their own Wi-Fi systems, there are several things to consider. The first is the funding source itself, which can be from existing funds, future revenues (bonds, loans, etc.), or grants. Grants are a one-time source and thus future years will need to come from other sources. Presuming a funding source is identified, there are hidden costs associated with wireless systems. The two major hidden costs are support and hardware refresh.

- Support is defined as the need to provide ongoing maintenance and service to keep the system running optimally. When Wi-Fi in a public space goes down, it will eventually be reported in some fashion to city officials and will require servicing to restore. That cost, therefore, need to be accounted for upfront. Who will provide the support? How will requests for service be addresses? What is the service level agreement (SLA) the city provides? Planning for this ahead of time will avoid costly outages down the line. Oftentimes, municipalities will contract with external partners to provide ongoing maintenance, but this comes at a recurring cost.

- Hardware Refresh is defined as the lifecycle of the network equipment. Five years after deployment, the Wi-Fi technology of the time will likely have been replaced with a newer generation. Municipalities must consider that future years will need to be budgeted for, otherwise the system could become stale and obsolete. With the General Fund model, municipalities should be clear-eyed about the ongoing refreshment costs and the commitment to upgrade equipment, as needed.

Lastly, when agencies self-fund Wi-Fi projects one of the largest future challenges they will face will be quantifying the benefits of the system over time. Just as it is hard to quantify the benefit of a new road or sidewalk, so it is with a Public Wi-Fi system. However, in order to continue justifying the expenditures, agencies should be prepared to analyze the real-world value their Public Wi-Fi system creates. Is it closing the homework gap and increasing students’ test scores? Is it providing a measurable uptick is measures of the local economy? Is tourism increasing? These are all questions that can be asked, and the answers could make-or-break a Public Wi-Fi system in the General Fund Model.

Wi-Fi as an Add-On to Another Project

Often, Wi-Fi is not an end-game, but a complimentary service that can be added to another, funded project. For example, a low-income housing project that has large political support may also provide an opportunity to include fiber-optics and Wi-Fi service in the immediate public spaces around it. Likewise, a transportation project such as a light-rail system could be the catalyst to deploy Wi-Fi along the service route. Many of these projects fall under the umbrella of “Smart City” technologies. The following list is by no means exhaustive, but in our research, we found General Fund model Wi-Fi projects that tied into such projects as:

- Smart lighting

- Cameras/surveillance/CCTV

- Fiber-optics, broadband build-outs

- Traffic signal build-outs

- Public safety technology projects

- Low income housing

- Internet of Things (aka “IoT”, where Wi-Fi can be an effective backhaul technology)

- Transportation projects like Light Rail or Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)

- Street beautification/improvement projects

- 4G cellular densification and small cell HetNet systems

Thus, municipal leaders interested in deploying Wi-Fi must observe projects going on throughout the municipality and effectively spot and present such “tie-on” opportunities. This requires inter- department/inter-agency cooperation and communication and even spread beyond a single municipality to a regionalized approach that explores opportunities with adjacent cities, mass transportation agencies, school districts, public utilities, parks districts, and more.

An important takeaway we have found is that Wi-Fi champions are often in the Information Technology departments and when these people are involved in decision-making (i.e., “at the table”) these “tie-on” opportunities are more likely to be capitalized on.

Conclusion

| Public Wi-Fi is now in a renaissance where new PPP models have been implemented, such as LinkNYC, while other agencies are successfully justifying expenditures from their general fund. |

Public Wi-Fi is now in a renaissance where new models and innovations have been implemented, such as LinkNYC, which are changing the perception of public-private Wi-Fi projects. Meanwhile, municipalities all over the country are taking Wi-Fi into their own hands and deploying systems that complement and even connect to other public-infrastructure, particularly in the smart city age.

Yet, while these funding and sustaining models may seem appear to be philosophically different – one approaches Wi-Fi as a revenue source to be installed and managed by for-profit enterprises while the other approaches Wi-Fi as a public service in the same vein as roads, streets, and public works infrastructure, the desires and intentions of the municipalities and officials behind them are nearly universal: to provide the public with free- high-speed wireless internet service. As such, there is no right or wrong answer to the funding model puzzle and neither model should be viewed as fundamentally superior to the other.

Which direction a municipality takes depends largely on local factors, such as the regional ecosystem, the size of the municipality, the location and density (rural/suburban/urban), the economics, and the public-private partnership (PPP) opportunities that are available. As a result, each Muni Wi-Fi project will look slightly different and no two will be identical.

Key Takeaways

- New “Revenue Fund” model projects in the form of public-private partnerships are yielding significant benefits to municipalities. There are many examples, such as: Sacramento’s exchanging city-owned assets like street lights in poles in exchange for Verizon putting Wi-Fi in city parks; and advertising-based systems like LinkNYC with no cost to the city that combine way-finding, Wi-Fi, charging stations and other services together.

- Yet, risk still must be managed in a PPP and answering the question, “What happens if it fails?” should be done in the beginning, not later. In addition, municipalities should take the time to find the right “fit” in a private partner.

- Meanwhile, “General Fund” model using public funds are flourishing, such as in San Leandro, CA and San Mateo County, CA. These projects tend to start on a smaller scale, targeting dense areas such as downtowns, tourist areas, and transit hubs. This keeps costs lower and allows expansions to happen over time.

- However, these projects must answer future funding challenges such as ongoing maintenance, support, hardware refreshment costs, while establishing data and metrics that continue accurately measure the benefits of publicly funded Wi-Fi systems.

- Wi-Fi can often be deployed successfully as a “tie-on” to other public projects, such as IoT; transportation; broadband/fiber; security and surveillance cameras; and more.

- City leaders who take up the mantle as “Wi-Fi Champions” must actively look for such opportunities both inter-agency, cross-departmentally and with regional public partners.