Emergency Preparedness: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "{{Chapter | blueprint = Public Safety | sectors = Public Safety | authors = Brenda Bannan | poc = Brenda Bannan | email = bbannan@gmu.edu | document = 2019-PSSC Blueprint 2019...") |

|||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

and response: prevention, mitigation, response, recovery and protection. Within these phases are | and response: prevention, mitigation, response, recovery and protection. Within these phases are | ||

identified analysis and assessment actions include: | identified analysis and assessment actions include: | ||

*[[CPG201Final20180525.pdf|Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA)]] – A four step common risk assessment process that helps a community develop a comprehensive hazard catalogue for threats and hazards of greatest concern, community defined desired outcomes, risk overview with hazard profiles and estimated impacts, and capability targets. There are 24 risk categories. | *[[Media:CPG201Final20180525.pdf|Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA)]] – A four step common risk assessment process that helps a community develop a comprehensive hazard catalogue for threats and hazards of greatest concern, community defined desired outcomes, risk overview with hazard profiles and estimated impacts, and capability targets. There are 24 risk categories. | ||

*[[ccds_all-mission-area.pdf|Core Capabilities Analysis]] – Communities engage in gap analysis planning efforts with capabilities falling into mission areas. As gaps are identified, specific needs emerge. Technology plays a role in helping EMs address these gaps within a core capability and across capabilities and in performing consequence analysis. | *[[Media:ccds_all-mission-area.pdf|Core Capabilities Analysis]] – Communities engage in gap analysis planning efforts with capabilities falling into mission areas. As gaps are identified, specific needs emerge. Technology plays a role in helping EMs address these gaps within a core capability and across capabilities and in performing consequence analysis. | ||

Technology solutions and innovations may enhance risk assessment through data collection and | Technology solutions and innovations may enhance risk assessment through data collection and | ||

aggregation, modeling, predictive analysis, and dashboard views. | aggregation, modeling, predictive analysis, and dashboard views. | ||

Revision as of 20:52, January 3, 2022

| Public Safety | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sectors | Public Safety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contact | Brenda Bannan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Activities

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Authors

{{{summary}}}

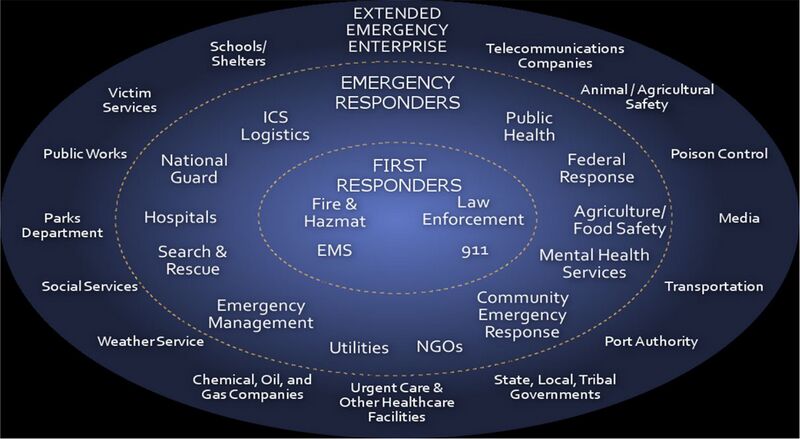

This section addresses the integration of traditional public safety and response into the broader scope of overall community preparedness, planning, and response. It deals with the development and coordination of multi-team systems of emergency response agencies with supporting and secondary organizations that interface directly with front-line responders during a disaster or civil emergency. Collectively, these organizations occupy the inner and second circles of Figure 2, and constitute the combined response capability of a community, jurisdiction, or region , and may be augmented by additional resources deployed through Emergency Management Assistance Compacts (EMAC) with adjacent states or jurisdictions or from federal sources, such as FEMA and other agencies.

For technology solution providers, this section provides insight into EM workflows and decision-making priorities. Industry may better address EM needs by understanding the concepts, frameworks, and language EMs use. Technology solutions should address identified gaps in a way EMs understand and manage crises and disaster operations. Therefore, this section begins with an overview of emergency management models and best practices that will inform development of a shared language for identifying and articulating fundamental EM requirements.

For EMs, this section provides insight into the relevant data, tools, and technology solutions available to meet their needs and ways to effectively evaluate and integrate technologies and associated protocols. Goals include:

- Improve EMs’ ability to evaluate and integrate S&CC/IoT technology into their emergency preparedness, management, and response processes—both for day-to-day operations (Blue-Sky days) and large-scale emergencies impacting multiple systems (Gray-Sky days).

- Enable technology solution providers to better understand and address EM needs through meaningful use cases by presenting EM frameworks and language.

- Suggest a collaborative, participatory process for design and integration of IoT solutions involving emergency management professionals, IT solution providers, and the community.

- Provide examples of how existing IoT technologies can help provide solutions to city challenges.

- Identify new vulnerabilities created by the connectedness of the previously unconnected first responder teams.

Key Characteristics

In general, the whole-of-community approach begins to have impact with emergency preparedness and management, where benefits from new technologies and the integration via advanced wireless networks supporting deployed sensors is most easily achieved. For preparedness, dual -use or multi-purpose technologies with utility in both Blue-Sky and Dark-Sky scenarios can achieve the greatest cost- effectiveness and potential for rapid adoption.

Key characteristics of the emergency preparedness and management approach to smart technology solutions include:

- More diverse opportunities for identifying and defining requirements to improve public safety (i.e., a bigger marketplace) and higher likelihood that technologies can be adopted without disrupting operational readiness of critical agencies and community functions;

• Connection with critical infrastructure systems already undergoing fundamental technology upgrades and transitions, including the adoption of high-speed wireless networks, embedded IoT sensors, data-mining and social networking platforms, resilient electrical grids, and general access to commercial enterprises that support these systems; • Close relationship with both commercial and public research and development institutes, and a willingness to accept a certain amount of risk in technology investment; and, • Risk of developing or adopting systems incompatible with current systems used by first responders and agencies, or that require fundamental changes in operating doctrine or procedures among those agencies. Integrating S&CC and IoT technologies into the emergency preparedness process brings opportunities (such as better situational awareness) as well as complexities (such as increased volume and variety of data) for emergency managers. As communities adopt smart technologies, they must rethink policies, operating procedures, and interagency planning and communications for all phases of emergency management to fully leverage new opportunities. Similarly, while the S&CC/IoT technical community has made significant advances in developing technology solutions, they must incorporate input and context- specific validation from emergency managers (EMs) and related personnel to fully meet user needs.

Emergency Preparedness Models and Best Practices

Two current models serve as sound examples of operational systems for organizing emergency management and response structures: the U.S. National Response Framework and National Preparedness System, and the international Cluster System adopted by the United Nations. Both represent best practice foundations and a shared language for identifying and assessing emergency management needs, and may be adapted for use in S&CC for potential IoT integration and innovation. Successful smart technology solutions will address specific needs jurisdictions may have within these frameworks. In either case, similarity with existing operationally tested frameworks is a virtue and should be pursued in U.S. and international applications within S&CC to the extent feasible.

U.S. Model

The U.S. National Response Framework/National Preparedness System (NRF/NPS) model establishes a single, comprehensive approach to incident management within the U.S. The NRF is used to achieve the National Preparedness Goal of a secure and resilient nation with the capabilities required across the whole community to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies. The NPS preparedness cycle comprises the five key phases or mission areas of emergency preparedness and response: prevention, mitigation, response, recovery and protection. Within these phases are identified analysis and assessment actions include:

- Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA) – A four step common risk assessment process that helps a community develop a comprehensive hazard catalogue for threats and hazards of greatest concern, community defined desired outcomes, risk overview with hazard profiles and estimated impacts, and capability targets. There are 24 risk categories.

- Core Capabilities Analysis – Communities engage in gap analysis planning efforts with capabilities falling into mission areas. As gaps are identified, specific needs emerge. Technology plays a role in helping EMs address these gaps within a core capability and across capabilities and in performing consequence analysis.

Technology solutions and innovations may enhance risk assessment through data collection and aggregation, modeling, predictive analysis, and dashboard views. Figure 6 shows the 32 core capabilities as they relate to the five mission areas of the NRF cycle. Hazard analysis is key to overall preparedness goals; planning and public information and warning are associated with all phases.

International Models

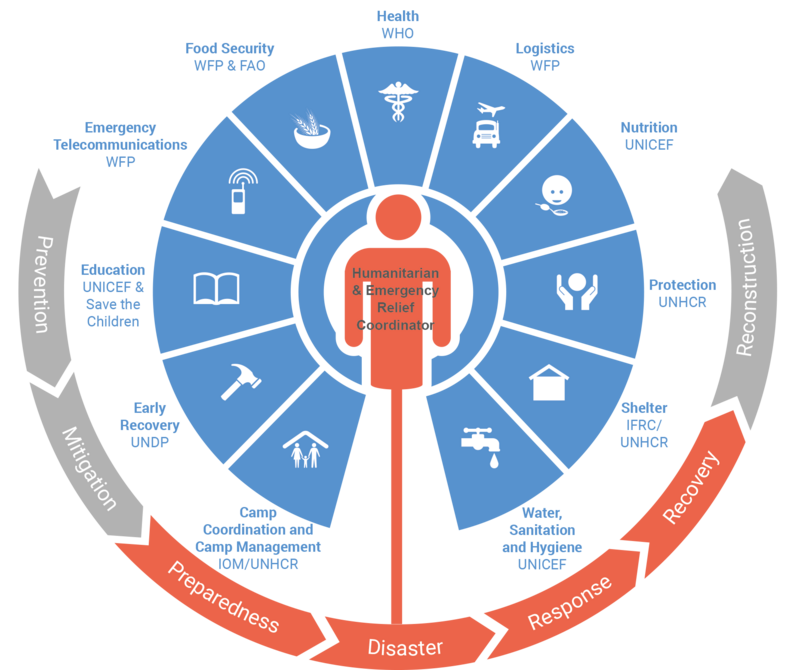

When a large-scale emergency occurs, the capacity of a city, state or national emergency management infrastructure may be insufficient to handle the response alone. Therefore, in the international space, when multiple organizations respond, effective coordination among response stakeholders is essential for meaningful emergency management. Good coordination stems from effectively involving multiple teams and stakeholders and minimizing gaps and duplications in the response work across organizations. However, the need of inter-agency coordination expands to all phases of the crisis management from prevention to reconstruction and it is the core of large-scale emergency preparedness. To address this complexity of coordination across the diversity of organizations involved (e.g., governmental vs. non-governmental vs. voluntary), the domain expertise and skills required, and the varied tasks, United Nations has proposed a Cluster System11 as shown in Figure 7.

According to the United Nations Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), the primary goal of this Cluster Approach is to strengthen system-wide preparedness and technical capacity to respond to large events or emergencies and to provide clear leadership and accountability in the main areas of emergency and humanitarian crisis response. At the nation level, it helps strengthen partnerships such as with the NRF in the U.S; and the predictability and accountability of international humanitarian action can be better understood with its help. By improving prioritization and clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of humanitarian organizations, the Cluster Approach has common features and synergies to NRF and NPS. The IASC guidelines and the UN Office of Coordination for Humanitarian Affairs emphasize:

- Supporting service delivery by providing a platform for agreement on approaches and elimination of duplication;

- Informing strategic decision-making for the humanitarian response through coordination of needs assessment, gap analysis and prioritization;

- Planning and strategy development including sectoral plans, adherence to standards and funding needs;

- Advocacy to address identified concerns on behalf of cluster participants and the affected population;

- Monitoring and reporting on the cluster strategy and results; recommending corrective action where necessary; and,

- Contingency planning/preparedness/national capacity building where needed and where capacity exists within the cluster.

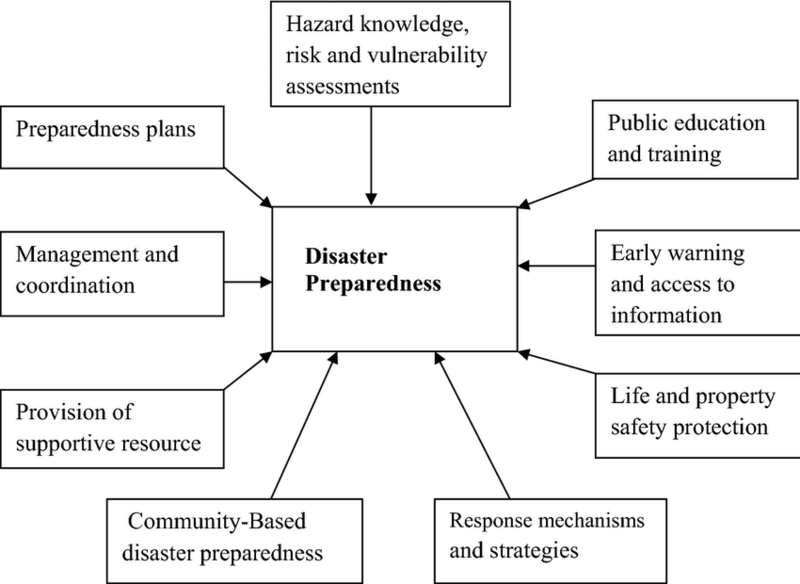

The Cluster Approach objectives are like those of the NRF. In addition, in the international disaster response practice, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Societies identifies the following elements in its comprehensive disaster preparedness strategic practices which can be adopted in a proposed model for defining preparedness requirements in a smart city context (Figure 8).