Disaster Recovery

| Public Safety | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sectors | Public Safety |

| Contact | Brenda Bannan |

| Topics | |

- Authors

This Focus Area of the Smart Public Safety initiative describes planning considerations for research and development (R&D) to enhance the ability of Smart & Connected Communities to efficiently manage the recovery of community functions and restoration of economic and social stability following regional or large-scale disasters and civil emergencies.

What distinguishes disaster recovery from response described in previous sections is that recovery is principally concerned with the identification, mobilization, and employment of community and private sector resources, rather than those of the professional responder agencies. In post-disaster recovery, the responsibility for restoration of critical infrastructure systems, continuity of governance and community services, and the recovery of economic stability and commercial activity rests largely on local government agencies and the civil population, itself. And unlike professional emergency response agencies, local government, the private sector, and civic leaders have limited opportunity to conduct training or coordinated exercises on community recovery, outside of continuity of operations planning within their own organizations.

Key Characteristics

The recent publication of the National Disaster Recovery Framework (FEMA 2014) has begun a process of "operationalizing" the whole of community approach that is fundamental to the recovery of a community after a disaster. However, the NDRF is a strategic document and provides little by way of actual guidance for community organization or planning. Specific characteristics of this area that relate to technology development and the application of smart city applications:

- Disaster Recovery is a new opportunity (i.e., a market) for technology development and integration. Public officials and private sector decision-makers currently lack the decision-making aids, data sharing networks, and operational protocols already in use by first responders through the National Incident Management System and Incident Command System.

• The Disaster Recovery area is amenable to research, technology development, and pilot testing unencumbered by the requirement for 24x7 readiness that response agencies must maintain. • However, there is little opportunity to conduct operational testing or piloting of recovery technologies or methods, since any operational employment will likely be under the most strenuous and critical of circumstances. Likewise, there is little documented experience to draw on for guidance or comparison. • The development and integration of technology systems or applications relating to disaster recovery will necessarily require compatibility with legacy systems of emergency management and first responder agencies, which play an active role in coordinating the transition from response to recovery, and also continue to serve public safety functions alongside agencies involved in the recovery of community services and public safety infrastructure.

Approach for Disaster Recovery in Smart and Connected Communities

As described in the two previous sections, the areas of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness principally involve professional disciplines of law enforcement, fire-fighting, EMS, and search and rescue that have specialized equipment, communications devices, vehicles and transport, and personnel protection equipment (PPE). These prof essions are supported by dedicated industry and commercial partners, and guided by professional, fraternal, and trade associations that define requirements, establish professional standards, and provide oversight in R&D and test and evaluation (T&E) of technologies and equipment. Within the last two decades, there has been a similar evolution in professionalization and the application of specialized technologies for Emergency Management and EOCs, particularly in the areas of information display and decision-support, geographic information systems and computer-based mapping, and improvements in connectivity and data sharing between operations centers and units in the field.

In contrast to the other sectors covered in this Blueprint, Disaster Recovery is largely the domain of authorities not specially trained in emergency procedures or disaster management, such as local and regional governmental authorities, the commercial sector, and the civil population itself. Unlike preparedness and response that are covered by NIMS/ICS, disaster recovery is guided only by the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF) published by FEMA in 2014, ten years after NIMS/ICS was adopted by the first responder community. While the NDRF provides a conceptual framework and planning factors relevant to community recovery efforts, the document does not provide a doctrine or methodology for community recovery efforts in the same way that NIMS standardizes disaster response and coordination. Disaster recovery is the responsibility of the community at large, for whom there is no current process grounded in decades of professional experience, documentation, and lessons learned.

Disaster recovery is an emerging discipline in the field of emergency management, and at this point is the least mature of the five functions of the incident management cycle (prevention, protection, response, recovery, and mitigation). As will be described in the next section on City Resilience, capabilities for effectively managing disaster recovery would contribute significantly to the overall resilience of a city or region. An effective, proven strategy for disaster recovery is thus one of the unmet needs in community resilience implementation.

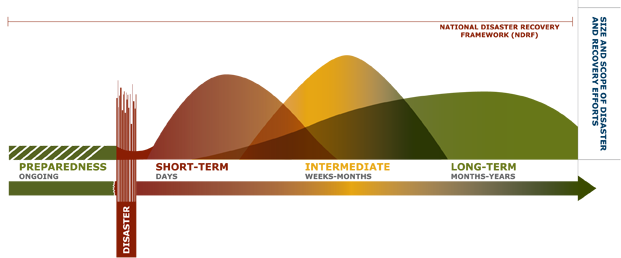

Figure 10 illustrates the timeline for disaster recovery, which can stretch from weeks into years, and remains the purview of the community, local government agencies, the private sector, and the affected population. Dedicated resources to restore normal community functions like school systems, the medical and public health infrastructure, the commercial sector and employment and tax bases are lacking.

Of greater significance than the lack of formal doctrine, is that no training program or certification process exists for the local government officials, community leaders, business owners, or citizens who suddenly find themselves in the role of disaster managers during the recovery phase. Unlike professional agencies such as fire-fighting, law enforcement, or emergency medical services, there is no ongoing training program to hone planning skills or “certify” a community and its leadership in disaster recovery. In reality, the process and skills are acquired through “on the job training” among community leaders during an actual disaster under the most stressful circumstances. Traditionally, every disaster recovery executed by a local community has been a one -off design developed by the community itself. An additional obstacle lies in establishing usable measures of effectiveness and metrics for determining which recovery approaches or strategies deliver the most benefit at the least cost, in both monetary and social terms.

A second challenge in the disaster recovery field is that public officials and community leaders who must recover a disaster-impacted community are rarely exposed to the challenges they will face in a disaster, except when it is suddenly thrust upon them. The challenge is not simply in designing and testing disaster recovery protocols and strategies, but in making them amenable to “just in time delivery” in the immediate aftermath of a crisis, when city officials, department heads, economic develop ment organizations, non-profits and volunteers, and community leaders must all determine the path forward for restoring their damaged community, based on little or no prior experience in the task.

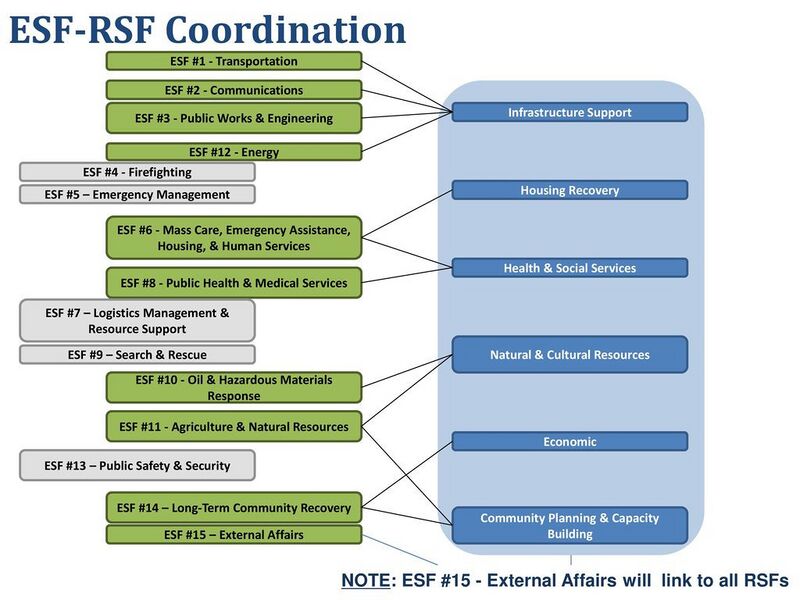

A useful approach for distinguishing the scope of emergency response from that of recovery is provided by the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) and Recovery Support Functions (RSFs) established by DHS and FEMA and articulated in the National Preparedness Goal and National Disaster Recovery Framework.

The ESF and RSF models describe a set of core capabilities and competencies in emergency response and disaster recovery (15 ESFs and 6 RSFs). While these provide a notably federal perspective on the scope of public safety, the ESF/RSF framework offers a useful structure for identifying areas of public safety where research and development of technology applications may achieve significant benefits for public safety and overall community resilience. Appendix A lists ESFs and RSFs and citations for the FEMA websites where the documents may be accessed.

The key challenge for ensuring capabilities for effective disaster recovery in S&CC is to provide technologies that can support multi-agency, community-level decision-making and collaboration under conditions when infrastructure systems are damaged or of limited availability, and numerous priorities compete for immediate attention. A planning assumption is that the NDRF/RSF approach should form the basis for future disaster recovery protocols and technology development efforts.

The following section addresses considerations for technology strategies to enhance overall City and Community Resilience, which in turn, also serve to build capacities for disaster response and recovery and overall public safety.