Public Safety and Response

| Public Safety | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Sectors | Public Safety | ||||||||||

| Contact | Brenda Bannan | ||||||||||

| Topics | |||||||||||

Activities

| |||||||||||

- Authors

This chapter addresses technology requirements definition, development, and deployment among traditional emergency services and first responder agencies—police and fire, EMS, search and rescue, and emergency management, particularly as employed in EOCs.

These agencies and services constitute the inner ring of Figure 1 on page 8.

After identifying organizations involved in daily public safety incident management, this section provides an overview of U.S. models for best practices. To strengthen consistency at the local, city, state, and national levels, operating best practices must be implemented consistently at each level to assist incident command centers, incident commanders and first responders from law enforcement, fire, EMS, and 9-1-1 Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) centers responsible for successful incident response. This section also provides input from the March 2017 PSSC Workshop, in which participants identified key requirements, resources, and guidelines for cities to effectively adopt smart technology in public safety and response.

Key Characteristics

Public safety and response agencies have specific advantages and limitations for adopting new and cutting-edge technologies. Factors influencing decisions to adopt new technologies include:

- Long-standing organizational histories, culture, and ethos, and a formalized operational doctrine within individual agencies and collectively through the NIMS/ICS structure;

- Specific technical and professional skills and a facility with integrating and deploying tested technologies and systems that add value to mission accomplishment;

- Demands and requirements for 24x7 readiness for emergency response that limit the ability to conduct operational test and evaluation, and customarily remove operating teams and management from direct involvement in research and development of new systems; and

- An institutional bias toward incremental improvements in tested and deployed systems, rather than adoption of cutting-edge technologies that could require technical and doctrinal change. This is an understandable result of these agencies’ 24x7 readiness posture, and to typically limited budgets that are directed to covering operational and contingency costs.

Priorities for technology solutions are focused on safety of individual responders and protection of mission effectiveness, communications interoperability between responder agencies, enhancing situational awareness between field units, incident command and EOCs, and improving decision-making based on real-time access and processing of data and situational reporting.

U.S. Models for Public Safety Response

Public safety officials and first responders—such as EMS, fire-rescue personnel, and law enforcement officers—need to share vital data or voice information across disciplines and jurisdictions to successfully respond to day-to-day incidents and large-scale emergencies. Many people assume that emergency response agencies across the nation are already technologically interoperable. However, first responders often cannot talk to some parts of their own agencies—let alone communicate with agencies in neighboring cities, counties, or states. To help address issues in interoperability and incident management, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has developed tools such as the Interoperability Continuum, National Incident Management System (NIMS), and Incident Command System (ICS), which support the foundation for a “Smart Public Safety” implementation. FEMA has defined NIMS and the supporting training for the ICS5 as a proposed national guideline for consistent operational implementation for public safety incident management.

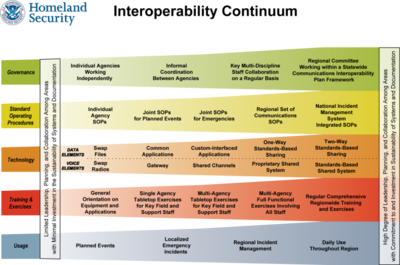

- Interoperability Continuum

Developed with practitioner input by DHS’s SAFECOM program, the Interoperability Continuum tool is designed to assist emergency response agencies and policy makers to identify five critical success streams that must be matured to achieve a sophisticated interoperability solution: governance, SOPs, technology (both voice and data), training and exercises, and usage of interoperable communications. Jurisdictions across the nation can use the tool to track progress in strengthening interoperable communications. Figure 4 provides a depiction of the Interoperability Continuum. To drive progress along the five streams of the Interoperability Continuum, emergency responders typically observe the following principles: • Gain leadership commitment from all disciplines (e.g., EMS, fire-rescue response, and law enforcement; • Devise the appropriate governance arrangements; • Foster collaboration across disciplines through leadership support; • Interface with policy makers to gain leadership commitment and resource support; • Use interoperability solutions regularly; • Plan and budget for ongoing updates to systems, procedures, and documentation; and, • Ensure collaboration and coordination across the continuum. Interoperability is a multi-dimensional challenge. To gain a true picture of a region’s interoperability, progress in each of the five inter-dependent elements must be considered. For example, when a region procures new equipment, that region should plan and conduct training and exercises to make the best use of that equipment.

Optimal interoperability is contingent on an agency’s and jurisdiction’s needs. The Interoperability Continuum is designed as a guide for jurisdictions pursuing a new interoperability solution based on changing needs or additional resources. One important factor to note about the continuum is that while organizations mature accordingly from left to right in each stream, for many agencies the third level in any given stream could be its desired end-state.

- Incident Management

While the Interoperability Continuum assists agencies in assessing their respective maturity in establishing communications and collaboration among multi-disciplinary teams, The National Incident Management System (NIMS) provides a flexible but standardized set of practices to manage incidents—with emphasis on common principles, a consistent approach to operational structures and supporting mechanisms, and an integrated approach to resource management. NIMS is a systematic, proactive approach designed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to guide departments and agencies at all levels of government, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector to work together seamlessly and manage incidents involving all threats and hazards— regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity—to reduce loss of life, property and harm to the environment. NIMS is the essential foundation to the National Preparedness System (NPS) and provides the template for the management of incidents and operations in support of all five National Planning Frameworks.

- Incident Command and Operations

Within NIMS, the [[Media:ics review document.pdf|Incident Command System (ICS)] is a management system that enables effective and efficient domestic incident management by integrating a combination of facilities, equipment, personnel, procedures, and communications operating within a common organizational structure (see Figure 5). ICS is normally structured to facilitate activities in five major functional areas: command, op erations, planning, logistics, intelligence and investigations, and finance and administration. This fundamental form of management enables incident managers to identify the key concerns associated with the incident— often under urgent conditions—without sacrificing attention to any component of the command system. Figure 5 illustrates the standard organizational structure that guide public safety agencies involved in mission critical incident management. There is not necessarily one department for each of the blocks below, but in most implementations, several organizational functions may be performed by one department or even one individual.

- Smart Public Safety and Response Implementation

- PSSC Workshop Outputs

Participants in the March 2017 PSSC Workshop explored how the Public Safety Interoperability Continuum, NIMS, and ICS needed to incorporate “Smart Public Safety” initiatives to to take greater advantage of the S&CC movement. Participants first defined the focus area scope, mission statement, and goals. They then identified requirements, existing resources, and technology solutions to be adopted, and action areas for cities.

- Scope and Mission

The Public Safety & Response Focus Area team defined its scope as: Identifying the problem statements, challenges, and solutions to existing governance, procurement rules, operating procedures, and technology integration to provide first responders, government officials, and other decision-makers with better situational awareness tools and information before, during, and after incidents in order to maintain community functions, ensure the safety of citizens, and protect the safety of first responders. Its mission was: Help first responders, public officials, and city managers use technology, processes, and collaborative data sharing and training to get the right information to the right people at the right time, in the most actionable format.

- Goals

Goals for the Focus Area:

- Draft the Blueprint/Playbook of guidance for cities to support improvements to situational awareness to ensure a common operating picture.

- Select a lead city to review and provide feedback on changes to the draft blueprint/playbook.

- Review the full listing of Action Clusters related to public safety and identify how Action Cluster initiatives/projects can be replicable.

- Goals for the Public Safety Blueprint

- Develop an inventory of assets (what does the community have and need).

- Ensure the quality, integrity, and harmonization of data between agencies and first responders.

- Support data analytics, utilization, visualization, and mobility to get the right information to the right people.

- Improve interoperable communications between agencies (including data, voice, and video capabilities).

- Support collaboration and coordination systems operating throughout the public safety incident cycle.

- Assist public safety agencies and community leaders in designing and distributing effective public messages, public service announcements (PSAs), and best practices to ensure an informed public.

- City Requirements

PSSC participants identified the following key requirements from communities for incident management within Smart Communities:

- Technology: Identify ecosystem requirements to support IoT, analytics, visualization, and mobilization of data, including devices, software, and applications.

- Cybersecurity: Develop principles for protecting IoT data and devices.

- Communications and Data: Support the interoperability of communications and data streams between agencies.

- Join standards that are currently uncoordinated.

- Normalize data (e.g., CAD system).

- Ensure the system is consistent and readable.

- Communications for Responders: Support mission critical voice, including moving from old to

new technology.

- Communications for Dispatch: Support an effective and enhanced dispatch system (i.e., Next Gen 9-1-1).

- Include texting capabilities.

- Enable management of the many types of data coming into dispatch centers.

- Support a feedback loop to help citizens act.

- Incorporate needs of the end users.

- Communications for the Public: Support public alerting systems (e.g., AMBER Alerts, geo-fencing).

- Include citizen-facing platforms to enable public alerting to disseminate critical information.

- Existing Resources to Meet Requirements

- Policy and Procedures

- Governance guidelines

- Operating procedures for incident operations and management (e.g., NIMS)

- GCTC Action Clusters and Community Groups

- Identify projects for the public safety sector (e.g., for NG 9-1-1; active shooter detection and defense; incorporation of unmanned aerial systems)

- Defining use cases (e.g., for cybersecurity)

- Financial Models

- Grants.gov portal for federal grant announcements

- NIST Public Safety Communications Research Grants (including the Prize Challenge)

- Partnership Models

- PPPs focused on interoperable communications Representative Technologies, Systems, Services and Solutions to be Adopted in Smart Communities

- Information Technologies

- IoT solution components

- Mobile solutions

- Cognitive solutions

- Cloud technologies

- Social Media data

- Video analytics solutions

- Communications

- Land mobile radio (LMR) systems and upgrades

- Satellite radios

- Fiber networks

- Deployable system communications

- Broadband and wireless

- Mapping and Location

- Geospatial information systems (GIS)

- Automatic vehicle location (AVL)

- Location-based service (LBS) tracking for phones

- Analysis

- Visualization (e.g., user interface, user experience [UI/UX])

- Data analytics (e.g., multi-modal biometrics)

- Information Sharing

- Computer-aided dispatch (CAD)

- Fusion centers

- Real-time intelligence centers (RTCCs, RTOCs, virtualized intelligence centers)

- Documentation

- Records management systems (RMS)

- Digital evidence management

- Shared portals

- Active Directory

- Federated Directory

- Master Name Indices

- City Requirements to Implement Smart Public Safety

Today, public safety agencies have many needs to implement a “Smart Public Safety” initiative. Workshop participants identified the following key action areas for cities:

- Reform procurement rules and funding mechanisms to support public safety technology investment.

- Encourage culture change to increase leadership and vision to implement technologies (a global issue).

- Funding is needed for training on technology.

- Leverage lessons learned' from major events to drive change (e.g., equipment modifications, governance and operating procedures, and collaboration).

- Focus on cross-agency planning and collaboration (e.g., establish working groups).

- Identify the return on investment (ROI) for executing use cases and case studies.

- ROI analysis

- Business plan

- Statement of benefit to the citizen

- Return on citizen investment

- Economic development

- Define the business case for investing in technologies.

- Encourage dual/multiple uses of technologies (emergency/non-emergency, safety/non-

safety).

- Define the safety case – will the technology help or hinder?

- Leverage test cases to prove the technology and reduce risk of implementation.

- Develop public-private partnerships.

- Focus on cross-agency collaboration and planning.

- Leverage the collaborative nature of jurisdictions.

- Include elected officials, including the mayor, city/county commissions, and boards.

- Define the value proposition of the technology investment and potential outcomes that positively impact the jurisdiction and/or elected officials’ platforms or priorities.