The Urbanization Challenge That Cities Face: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Chapter | {{Chapter | ||

| | |image=ProblemChapter.jpg | ||

| | |poc=Scott Tousley | ||

| authors = Scott Tousley, Jason Whittet | |authors=Scott Tousley, Jason Whittet | ||

| | |blueprint=Introduction | ||

| | |sectors=Introduction | ||

|summary=Cities are facing a crisis. If you ask most Mayors what they want for their cities, they will say “jobs, economic growth, a healthy vibrant and safe community that offers an inclusive high quality of life for all of its citizens.” But to accomplish these things, a city must plan and manage its assets efficiently, to include it most precious asset – its people. | |||

|email=tousleys@gmail.com | |||

|document=20170824-City-Platform-Supercluster-Report-FINAL.pdf | |||

| summary = Cities are facing a crisis. If you ask most Mayors what they want for their cities, they will say “jobs, economic growth, a healthy vibrant and safe community that offers an inclusive high quality of life for all of its citizens.” But to accomplish these things, a city must plan and manage its assets efficiently, to include it most precious asset – its people. | |chapter=3001 | ||

}} | }} | ||

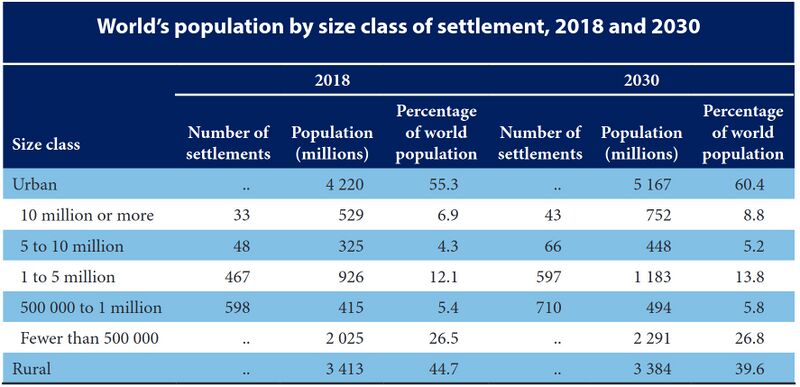

People are flocking to cities at a rate of three million people moving into urban areas each week. In 2016, an estimated 54.5 percent of the world’s population lived in cities. By 2030, urban areas are expected to house 60% or more of all people globally and one in every three people will live in a city with at least 500,000 or more inhabitants. | People are flocking to cities at a rate of three million people moving into urban areas each week. In 2016, an estimated 54.5 percent of the world’s population lived in cities. By 2030, urban areas are expected to house 60% or more of all people globally and one in every three people will live in a city with at least 500,000 or more inhabitants. | ||

Latest revision as of 22:40, January 19, 2023

| Introduction | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sectors | Introduction |

| Contact | Scott Tousley |

| Topics | |

- Authors

Cities are facing a crisis. If you ask most Mayors what they want for their cities, they will say “jobs, economic growth, a healthy vibrant and safe community that offers an inclusive high quality of life for all of its citizens.” But to accomplish these things, a city must plan and manage its assets efficiently, to include it most precious asset – its people.

People are flocking to cities at a rate of three million people moving into urban areas each week. In 2016, an estimated 54.5 percent of the world’s population lived in cities. By 2030, urban areas are expected to house 60% or more of all people globally and one in every three people will live in a city with at least 500,000 or more inhabitants.

Additionally, the number of megacities (defined by populations of 10 million inhabitants or more) will swell 32% from 31 to 41 by 2030. The urbanization challenges these megacities face can be even more complex to deal with if you have both a high population and a high population density city. While high populations create high stress workloads on existing city infrastructure, the high population density cities face this reality along with often being at an economic disadvantage. Cities like the Bangladeshi capital of Dhaka, have 14 million residents squeezed into an area of 125 square miles, making for a population density of 115,000 per square mile.

There is a widely accepted idea among urban core theorists that higher population densities lead to more productivity and sustainable economic growth. This is, in fact, not the case. While it is true that higher population cities often have higher GDP’s, there is an imperfect if not inverse relationship between density and wealth as defined by city GDP. Cities that have larger populations spread out over larger land masses tend to fare much better than those megacities with densities like Dhaka, Mumbai, Karachi and Delhi. Without a healthy GDP, there is less tax base for cities to tap into to pay for city services. This economic strain can have a ripple effect, as the worse that a city performs in providing services, the harder it is for a city to attract and retain its inhabitants. One of the greatest economic drivers for a city is its people, and without proper support of its people a city will not rise to its greatest economic potential. The challenges that megacities with higher population densities face are very complex, and cities like this especially need to actively seek solutions to their challenges.

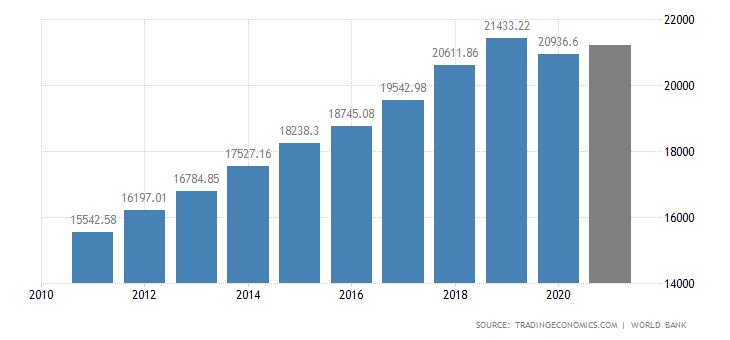

Since 2009, the US economy has generally improved but many cities face constrained budgets because of weak property tax revenue growth and cuts in federal and state financial aid.

In many communities across the US, the existing infrastructure is already stressed, yet there is less money available to invest in maintenance, upgrades or replacement. Cities are faced with tough decisions on how to deploy their capital. Should deferred maintenance be done only when the most dire circumstances exist? Should routine, scheduled maintenance be done to preserve current levels of operational efficiency and extend asset life? Or should investments be made in modernization of infrastructure that can yield operational cost savings, or potentially even create revenue streams? There is no clear answer.

While cites are doing their best to manage historically well understood demands, there are also new emerging challenges that cities are facing. Problems associated with urbanization, such as power grid challenges, transportation and mobility challenges or public health are new concerns for city officials. Also, the threats against public safety from domestic terrorism and cybercrimes pose new challenges for cities to address with limited budgets. How do cities assess the worthiest capital investments? And once made, how are these investments measured for success? Much of the answer lies within data.