Benefit, Value and Return on Investment (ROI) Considerations

| Introduction | |

|---|---|

| Sectors | Introduction |

| Contact | Benson Chan |

| Topics | |

- Authors

Smart buildings are one “bottom up” component of a smart city. They incorporate advanced and integrated digital technologies, algorithms and analytics, to bring new and significant value to tenants, building owners and operators. These benefits range from increased tenant productivity, comfort, a safe and healthy environment, lower operating costs, and higher satisfaction. While the benefits and Return on Investment (ROI) of smart buildings are well documented for tenants, occupants, and building owners and operators, similar information for cities is limited at best.

Introduction

The emergence of next generation technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), telecommunications (public and private LTE networks, 5G, Wi-Fi improvements, LPWAN, etc.), and data science, are poised to transform today’s cities into advanced smart cities. These cities are more resilient, safe and secure physically and digitally, healthier, economically vibrant, have a higher quality of life, and are more attractive to their residents, businesses and visitors. As an example, the city-nation of Singapore, is leveraging its considerable digital infrastructure to build an advanced smart city to support the current and future needs of its 5.5 million citizens in a very dense urban setting. Despite these benefits, building a smart city is a complicated and expensive multi-decade undertaking.

Many cities take a top down approach to building a smart city. However, this approach brings several challenges. It takes a lot of time and vision, require coordination and agreement with a large number of city stakeholders who often work in silos, and significant political support and funding. Committed resources and funding are often pulled to support new priorities of incoming political and city leaders. Top down approaches are multi-year journeys often lasting well beyond the term of political tenures.

Against these realities, an organic bottom-up approach is necessary to complement the top-down efforts. A smart city is not built all at once, but one block, one park, one building, one neighborhood, one community at a time. Bottom up approaches enable manageable smart city development that are aligned to current needs, priorities and available funding sources. They involve a smaller group of stakeholders, a narrow set of priorities and outcomes, and move much faster than a top down approach.

Smart buildings are one “bottom up” component of a smart city. They incorporate advanced and integrated digital technologies, algorithms and analytics, to bring new and significant value to tenants, building owners and operators. These benefits range from increased tenant productivity, comfort, a safe and healthy environment, lower operating costs, and higher satisfaction. While the benefits and Return on Investment (ROI) of smart buildings are well documented for tenants, occupants, and building owners and operators, similar information for cities is limited at best.

This is because the role and value of smart buildings in a city has not yet been defined or understood from a municipal perspective. Understanding this perspective requires answering the following questions: * What role do smart buildings play in smart cities?

- What value do cities get from smart buildings?

- Why should city officials and residents want smart buildings in their cities?

- Why should cities encourage the development and retrofitting of smart buildings?

- How do the value that smart buildings bring to its owners, operators, tenants and occupants translate to value for cities and communities?

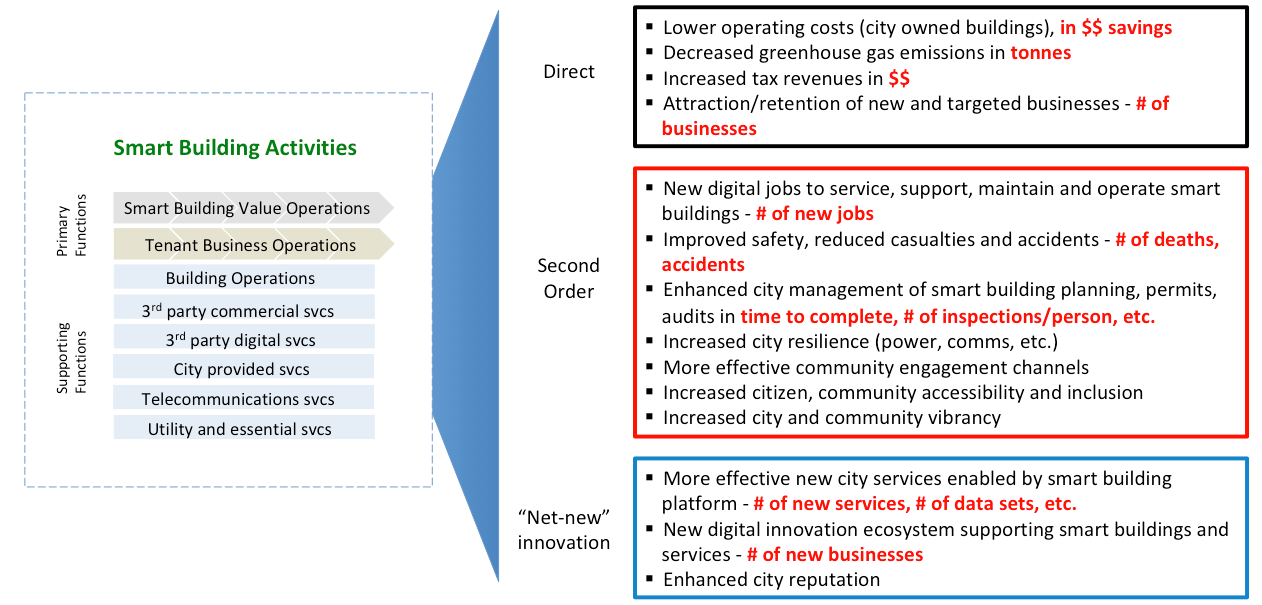

This chapter provides an approach for defining the value offered by smart buildings from a smart city perspective. It starts with a discussion of the eight outcomes that cities care about, and the four civic dimensions these outcomes are evaluated against. A framework (Figure Six), describing the activities enabled by a smart building, is then introduced that aligns these activities to the outcomes. A second framework, correlating the eight outcomes with the four civic dimensions, provides the necessary structure to identify and capture the smart building benefits and value that the cities care about. The chapter concludes with a sample set of these benefits mapped into the second framework (Figure Eight).

What Do Cities Care About?

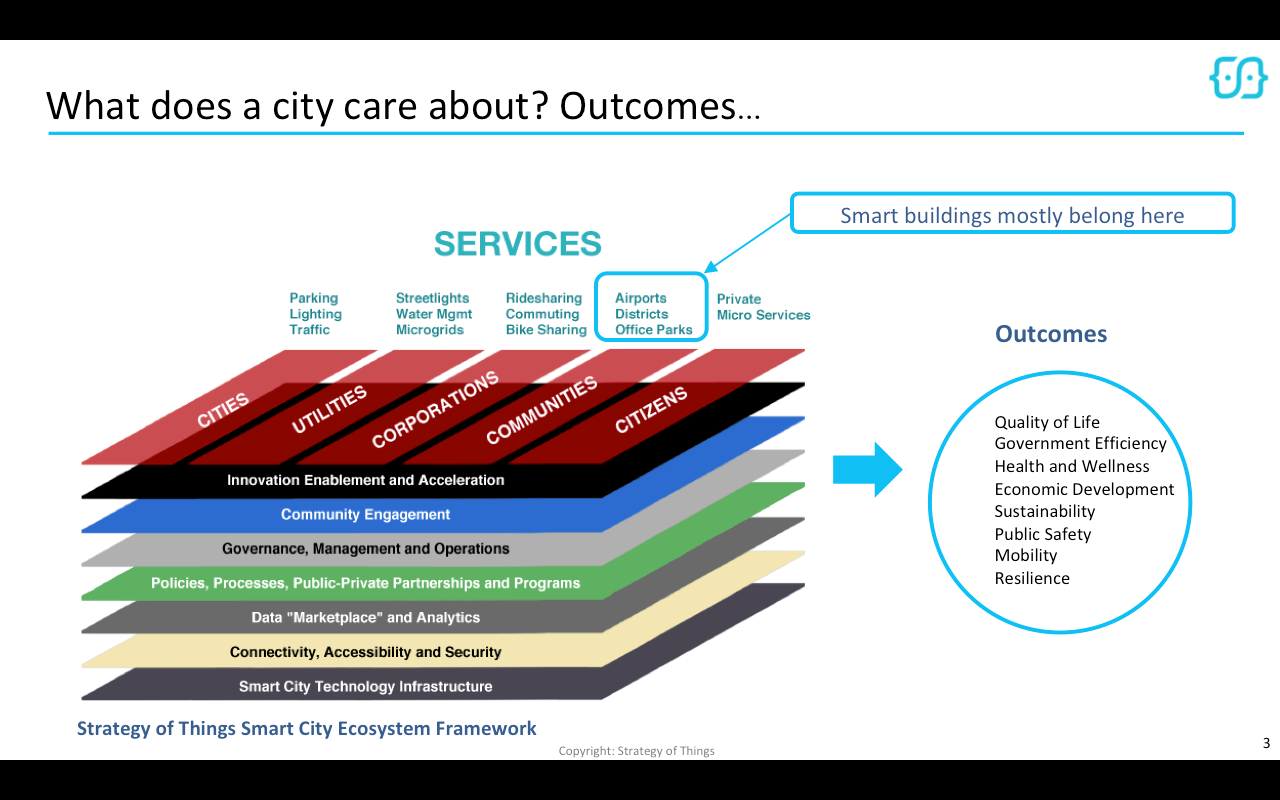

Cities are dynamic entities with diverse constituents and complex geographical, economic and political needs. In order to understand how cities benefit from smart buildings, we begin with some background and understanding of the drivers of civic value. We will start with the things that cities care about (civic outcomes), who creates these outcomes (outcome providers), and how the value for these outcomes is quantified and evaluated by city stakeholders.

Ultimately, these interconnected outcomes must lead to the ultimate overall ROI for a city - a place that is healthy, productive, safe, self-sustaining and attractive over time, and where citizens and businesses choose to live and operate in.

City Outcomes

A city, large, medium or small, is in the “business” of creating and maintaining civic outcomes[1] for its residents, businesses and visitors (Figure One). Civic outcomes reflect social, economic, health or political needs. A civic outcome is streets that are safe for pedestrians and bicyclists. Another example could be access to affordable housing for low income families and fixed budget senior citizens. A third example outcome could be access to affordable digital connectivity and services, supermarkets, and healthcare services in underserved neighborhoods.

While all cities care about these outcomes to a certain extent, some outcomes are more relevant to them than others. Each city is unique, and its focus on specific civic outcomes reflect its unique economic, geographic, political and temporal priorities, and the needs of its many constituents. For example, economic development is a priority for some cities, while public safety and quality of life are more important for others. These outcomes are documented in a city’s strategic vision and plans, codified in its policies and regulations, and implemented in the form of funded initiatives and programs.

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 has disrupted and devastated cities and communities worldwide. From the loss of lives, overwhelmed health care facilities, interruption of essential day-to-day services, to disruption of the global economy, no one is spared. For example, in many cities, emergency declarations are made and a “shelter in place” is ordered for the general population to stay home. Schools are closed and in-class instruction has shifted to distance and remote learning. Non-essential businesses are closed or operating remotely, and enabling new modes of working that were not considered before. Mass public gatherings and events are banned. Face to face interactions and transactions are conducted at “social distances”.

In light of the disruption to cities and communities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, public health outcomes are now top of mind. More importantly, the pandemic has caused a dramatic rethinking priorities and outcomes for the years ahead. Cities who have not prioritized resilience, health and public safety outcomes are now focused not only on these outcomes, but on driving economic rebuilding and recovery.

City outcomes are created by an ecosystem of “outcome providers”

City government is not alone in creating civic outcomes. Civic outcomes are created, delivered and maintained by an ecosystem of five groups of “outcome providers” – cities, utilities, corporations, communities and citizens (Figure Two).

Each “outcome provider” is responsible for delivering outcomes within its scope and domain. For example, the city is responsible for such things as maintaining streets, traffic signals and parks, while utility companies are responsible for gas, water and electricity. In other areas such as mobility, the city and private companies collaborate together to provide bus service, taxis and ridesharing, scooters, bicycles, and on-demand specialized transport services. This provider ecosystem works collaboratively to deliver certain synchronized outcomes in some cases, while working independently with limited to no collaboration in others.

Supporting these city “outcome providers” is an infrastructure composed of people, organizations and businesses, policies, laws, processes and technology integrated together to create the desired outcomes. The responsive civic ecosystem is adaptive, agile and always relevant to all those who live, work in and visit the city. When advanced digital technologies, such as IoT, AI and analytics, are incorporated and integrated into this underlying infrastructure, new disruptive and transformational civic outcomes are created.

In this civic ecosystem model, the smart building is an outcome provider to the city. In order to be relevant to the city, smart buildings must create those outcomes that cities care about, and to do it in ways not possible before, or with less cost, greater efficiency, and fewer resources.

City outcomes are measured differently

In business, ROI is a common metric used to determine whether a new initiative should be undertaken, how existing ones are performing, whether those should be continued, and what new resources should be applied. As a business has many competing initiatives and priorities, management allocates its limited resources to those that generate the highest returns, financial or otherwise. Except in strategic instances, business initiatives typically meet a minimum ROI threshold to be considered or to continue.

In contrast, cities are not businesses. Cities have different goals and “business models”. They do not create revenues to make a profit, but to produce, maintain and enhance city services. Cities create services and often solve problems that have negative ROIs but serve a “common good”, such as to promote community vibrancy rand economic growth. They serve “customers” and stakeholders, as well as sectors and communities that businesses do not find profitable to service. Their main source of “revenues” is from taxes, as well service fees (parking, citations, administrative fees, etc.), designed to offset the cost of providing the various services. As a result, the concept of ROI for cities need to be redefined and viewed through a different perspective. This is done by examining the set of activities that a smart building conducts or enables and mapped against the eight city outcomes (Figure Six). The mapped value of these activities is further evaluated and categorized against the four civic dimensions (Figure Four) and placed into the smart building value framework (Figure Eight). These models are explained in the sections below.

Cities focus on creating city outcomes (Figure One). In addition to a ROI based solely on financials, cities also evaluate a ROI based on effectiveness of the delivered city outcomes. For example, some considerations and metrics cities care about include:* How many new jobs were created?

- How much crime was reduced?

- How many lives were saved due to a faster response time, and/or more accurate location information?

- How many homeless has the city taken off the streets?

- How effective was the city in getting communication participation on key issues?

- How effective was the city in responding to and limiting loss of live and property from natural or man-made hazards, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, or civil unrest?

- How effective was the city in responding to and mitigating an unplanned health emergency, such as the COVID-19 outbreak?

The ultimate overall ROI for a city is that its initiatives and programs lead to a place that is healthy, productive, safe, self-sustaining and attractive over time, and where citizens and businesses choose to live and operate in.

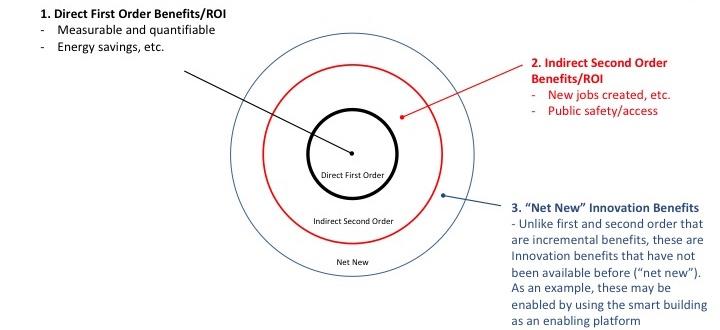

City outcome ROIs fall into three categories

The benefits, or value provided, by city outcomes cannot always be easily quantified. The ROI for creating outcomes fall into three categories[2] - direct benefits, indirect or second order benefits, and innovation benefits (Figure Three).

Direct benefits are those benefits that arise as a direct consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service in creating a civic outcome. For example, when a city deploys a smart and connected streetlight system, the immediate benefit is awareness of the state of every streetlight. This leads to the elimination of personnel needed to drive around the city at night manually looking for broken lights and results in lower streetlight maintenance costs. Direct benefits are directly correlated to the initiative, and are typically easily quantifiable.

Indirect benefits are those that arise from a secondary consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service. For example, because the smart and connected streetlight system eliminated the need for personnel to drive around looking for broken lights, the same personnel can be redeployed to work on other city projects. The result is that the city can now do more with the same amount of people and budget. Depending on the specific benefit, indirect benefits are generally quantifiable (although not always as easily).

Innovation benefits are created from additional services that “piggyback” onto the newly implemented smart building infrastructure and capabilities to create new offerings. For example, the infrastructure of the connected and smart streetlight system can support other smart city systems. Sensors, including cameras, can be mounted on top of the system controller at the top of the streetlight. Wi-Fi access points, can also tap into the power source and connectivity, on the existing streetlight system controller to provide local Internet service. These innovation benefits (and the services that create it) are not always known at the time the smart building is planned or constructed. These benefits fall into the “unknown unknowns” and are not easily quantifiable, nor do we always know when they will be “activated”. However, innovation benefits are real and must be specified (when known) and taken into consideration, even if they cannot be quantified.

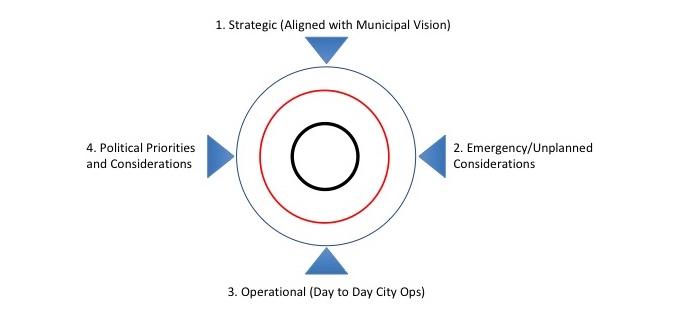

Civic outcome ROIs and benefits align to one of four civic dimensions

Smart buildings, one of the building blocks of a smart city, create similar tangible direct, indirect and innovation benefits and ROI for a city. What those benefits are, and how they are activated and valued varies from building to building, building type to building type (public, commercial, residential, industrial, etc.), and city to city. Each city is unique, and its focus on specific civic outcomes reflect its unique economic, geographic and political priorities, and the needs of its many constituents. Cities have a diverse set of stakeholders with differing perspectives and priorities. These stakeholders hold differing perspectives based on their roles, responsibilities, goals, and constituents.

Figure Four shows the four dimensions that outcomes and benefits are reviewed against. There is no one single view of an outcome - different stakeholders within the municipal ecosystem will be looking at the outcomes from one of these perspectives.

The strategic dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with a city’s long-term vision and strategic needs. Many of these priorities are documented in a city’s general plan or vision document. These priorities are translated to specific initiatives which are implemented over the plan’s lifetime (typically 10 to 25 years).

The operational dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with the day-to-day “run the city” activities and how well the city is able to provide services effectively and efficiently. These operational priorities vary from city to city, and are focused on resources, capabilities, costs, productivity and responsiveness. These priorities and needs are captured in each city department’s charter document and its operating plan.

The political dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with the long term and day-to-day electoral, governance and legislative needs of the city. It reflects the priorities of the political leaders and the citizens who elected them. These priorities may not always align with the city’s strategic and operational priorities. At other times, they may be consistent with the city’s strategic priorities, but not aligned on when they should be implemented. These priorities are typically documented in the campaign platform or promises that political leaders got elected on, and addresses the specific needs of their constituents.

The emergency or unplanned dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits (also known as resilience dividends) are aligned with the resilience capabilities and resource needs of the city when something unexpected occurs. For example, a natural or man-made disaster, a massive event, or some other crisis event. These needs may be captured in the city’s and department’s resilience planning documents. With the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, this dimension is now top of mind. Key considerations consider how the outcomes can prevent future outbreaks, protect and mitigate against current infections, limit adverse financial and economic impacts to the community, and respond to and recover from the pandemic.

When selling the value and ROI of smart buildings to municipalities, one must understand not only what direct, indirect, and innovation benefits are offered to the city, but also how these benefits are aligned to the four civic dimensions.

Where Do Smart Buildings Offer Value to Cities?

In the last section, an understanding of the types of outcomes cities care about, the role of ROI and types of benefits, and how those benefits are viewed against the four civic dimensions were provided. In this section, potential sources of smart building value creation for cities are discussed.

Smart buildings and cities come together at interaction points

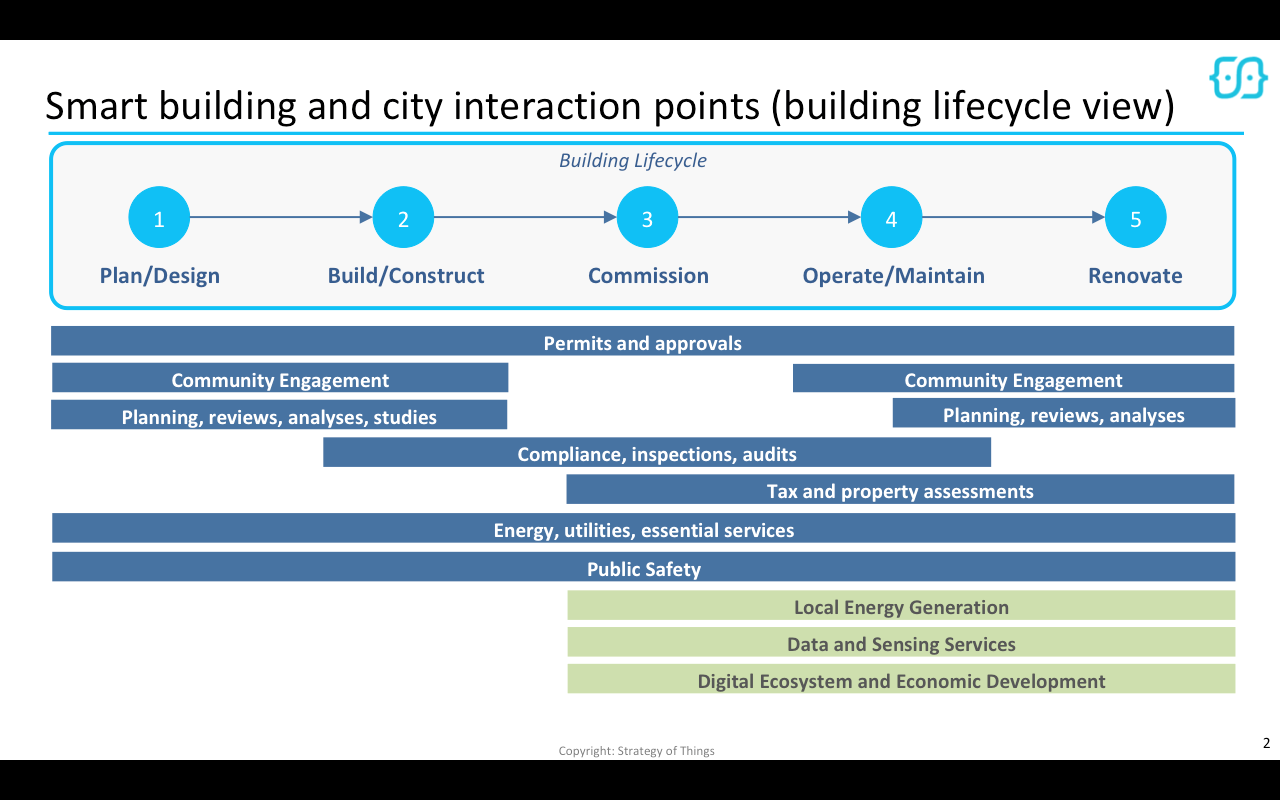

Figure Five identifies the major interaction points between the smart building and the city over a typical building life cycle[3]. At each stage of the building life cycle, a different set of activities, and interactions, are involved between the smart building, the city, and others in the civic ecosystem. Some of these interactions are identical to those that exist between the city and traditional buildings. However, smart buildings provide additional interactions (highlighted in green), enabled by their advanced energy and digital infrastructures and capabilities. These interactions create new opportunities for value to the city.

These smart building-city interaction points provide the path or channels for the delivery of benefits to the city. But what exactly does a smart building do to create the value that is transferred to the city through these interaction points?

Smart buildings create value through direct and indirect activities

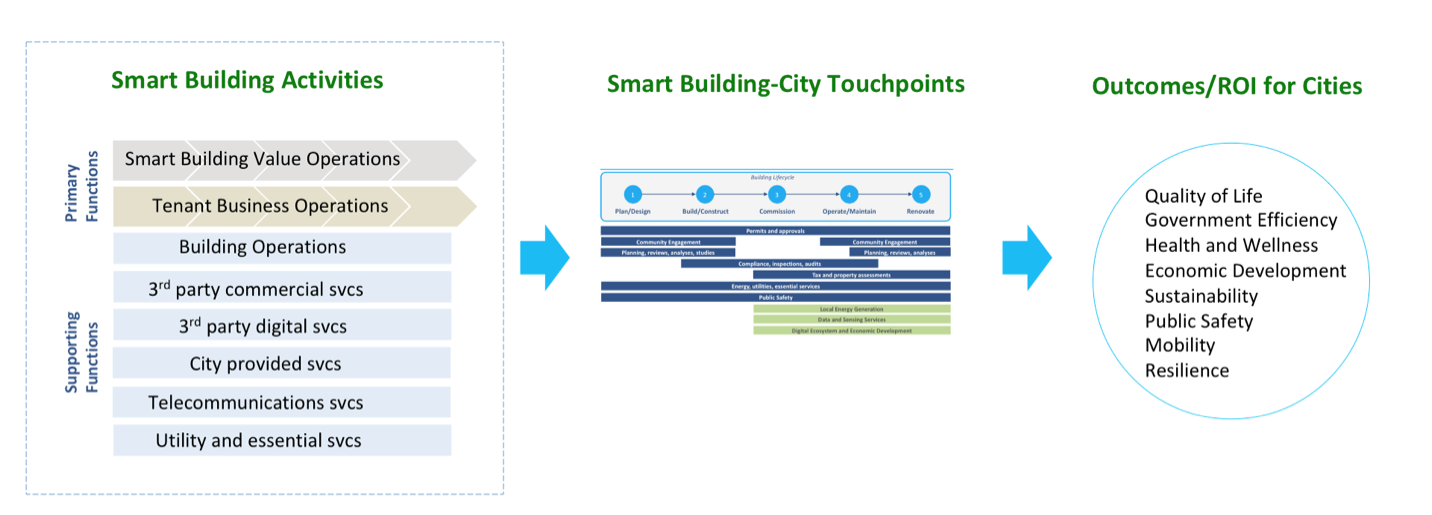

Civic value creation in a smart building comes from three distinct sets of activities (Figure Six). Tenant business operations and support activities create tangible value for the city indirectly as it carries out its non-city task. On the other hand, smart building value operations are those services directed at the city as the customer.

A smart building creates value by enabling its occupants to work more effectively, productively and safely on a day-to-day basis than in a non-smart building. For example, a smart building may incorporate controls that adjust the lighting levels to match the daily circadian rhythm helps to reduce occupant drowsiness, improve mood and concentration during working hours. This building may incorporate occupant personalization technologies, such that when they schedule a conference room, the climate control systems adjust to account for the number of people, the teleconference and audio/video systems are already configured for the meeting, and digital resources for the meeting are routed to this room.

In light of the COVID-19 outbreak, smart buildings have taken on a new and vital role – to keep its occupants healthy by avoiding and minimizing exposure to the virus. Sensors can detect people with a high body temperature and prevent them from entering the building. Security camera feeds, combined with AI algorithms, monitor social distancing and face mask compliance. Contact tracing applications, based on bluetooth radios located on employee badges and personal mobile devices, facilitate notification of people who may have been inadvertently exposed. Sanitizing robots autonomously clean heavily trafficked areas on regular intervals. The extensive use of these technologies in response to the pandemic raises issues of effectiveness versus personal privacy and consent.

In increasing productivity, health and safety, these occupant tenant activities directly or indirectly contribute new (or more) value for the city that it couldn’t have offered otherwise. Tenants are more likely to seek out smart buildings, stay in them longer, be more willing to enter into premium leases, and more likely to locate, expand and hire more employees. This in turn leads to higher assessed building assessed values (and surrounding buildings) and higher property tax revenues for the city. At the same time, a more productive tenant contributes to the development of the local businesses, which leads to increased tax revenues generated from the business ecosystem.

A smart building has a more robust and advanced digital and communications infrastructure than a non-smart building. Its excess capacity can be used by the building owners to create direct outcomes for the benefit of a city. Unlike occupant activities which indirectly benefit the city, the smart building value operations are activities that are specifically designed to leverage the building’s capabilities and infrastructure to provide direct value and outcomes to the city. For example, the smart building may leverage any excess capacity on this infrastructure to provide data and sensing services to the city. It may do this by hosting an Internet of Things (IoT) sensor network to monitor outside pedestrian and motor vehicle traffic around the building. It may integrate with other nearby smart buildings to extend a citywide communications network infrastructure. It may utilize its analytics and data processing capabilities to review the sensor information, create actionable insights, and provide the data directly to the city or the community. A smart building may use the excess energy produced by its solar panels and provide it back into a local microgrid to meet the demand of its neighbors.

Smart buildings facilitate tenant operations and smart building value operations through a series of support activities. These range from building maintenance operations to telecommunications services. In a smart building, these supporting activities will also contribute to the attainment of city outcomes. For example, the operation of the smart HVAC system, designed to keep building occupants comfortable, results in decreased energy usage and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The smart HVAC system, heavily dependent on a new generation of digitally savvy engineers, integrators and service technicians, results in new “smart” jobs and a supporting digital vendor ecosystem, and creates economic development outcomes. The operational aspects and considerations of smart buildings is described in more detail in a later section.

Sample Smart Building Value and Benefits for Cities

To discuss the benefits of smart buildings to a city, consider a community level metric. A community with a “positive tipping point” of smart buildings leads more easily to being considered a “city of the future.” A few smart buildings can attract new talent, workforce and positive tax-flow, but by themselves are not enough to create a connected, Smart City. A more unified approach is needed. The city of Henderson, Nevada[4] is a good example of a city where the build-out is thoughtful along all 8 outcome dimensions, and as a result is the 3rd fastest growing destination for businesses and relocating individuals in the country at this time.

Using the above model and considerations, review the smart building activities against the city-building touchpoints to identify potential ROI and benefits (Figure Seven). This is not a comprehensive list and there will be additional benefits beyond the initial set listed. It is left to the reader to identify those that may be unique to their city and smart building(s). The benefits in Figure Seven are further classified into the three categories defined earlier in Figure Three.

Direct Benefits

- Lower operating costs for city owned buildings that have been converted to smart buildings (in $$ savings). Depending on the type of smart building and the number of modifications and extent of “smart”, the city may realize varying levels of operational cost savings. These cost savings may come from lower energy costs, reduced number of security, maintenance personnel required to service the building, and lower insurance costs due to a lower risk profile.

- Decreased greenhouse gas emissions (in tonnes). Smart buildings use less energy, and as a result, the amount of heating, cooling required is a lot less in a smart building. Buildings operations generate a lot of greenhouse gas within the city. By reducing and more importantly, optimizing energy usage, a lot less greenhouse gases are generated and released. It is estimated that a smart building uses 30 to 40% less energy than. In addition, smart buildings facilitate “green” transportation options, from infrastructure that natively supports electric vehicles, integration with public transportation and ridesharing, or with future air mobility options.

- Increased tax revenues (in $$). A smart building is a desirable real estate asset for building owners. The smart building allows tenants to work in a more productive, comfortable and safer environment. As a result, the smart building attracts premium tenants, who are more likely to sign longer leases, pay higher rents, and are less likely to leave. For a city, this increases the building’s assessed value, and the corresponding property tax revenues.

- Attraction/retention of new and targeted businesses (in # of businesses). A smart building attracts premium tenants. These types of tenants may be consistent with the mix of businesses the city wants to attract as part of its strategic plans. For example, a city wishes to attract high paying jobs typical in technology, financial services, research and healthcare businesses. In turn, these premium businesses attract an ecosystem of secondary businesses to directly and indirectly support and service them.

- Healthy workspaces enable employees to work in the office and ensure on-site business continuity (in # of vacancies). A smart building enables its occupants to work in a safe and healthy environment. For example, these buildings may implement a variety of technologies to limit exposure and transmission of airborne contagions, such as COVID-19. This facilitates in trust and confidence in building tenants and occupants, and allows businesses to physically open and operate. As a result, the smart building will be more desirable as it attracts new tenants and retains old tenants. Tenants are likely to choose smart buildings and pay a premium rate for these spaces.

Indirect or Second Order Benefits

* New digital jobs to engineer, design, service, support, maintain and operate smart buildings (in # of new jobs). Smart buildings operations require additional new skills and capabilities not needed with traditional buildings. These skills include networking, advanced telecommunications, cybersecurity, application development, multi-systems integration, information technology/operations technology (IT/OT) integration, and analytics. As more smart buildings are built (or retrofitted), the demand for these new jobs will continue to increase. New jobs (and training programs) will be created to fill these high demand digital positions.

- Improved safety, reduced casualties and accidents (in # of deaths, injuries, accidents reduced). Smart buildings employ a variety of innovative solutions to protect its occupants and those who work and maintain the buildings. From high performance access control systems, advanced fire management systems to sensors and predictive algorithms, to remote monitoring of critical systems and integration with public safety access points (PSAP), and informed sharing of real time data and conditions before arrival on scene, smart buildings facilitate safer working conditions and more effective first responder responses. In addition, smart buildings can interact with nearby smart buildings to proactively notify its occupants of nearby public safety incidents and take necessary precautions.

- Enhanced city management of smart building planning, permits, audits in time to complete (in # of inspections/person, time, and accuracy). From initial reviews to annual safety inspections, smart building sensors, systems, and algorithms can facilitate and automate (to the extent possible) inspections, compliance reviews and audits. This capabilities facilitate “smart processes” which enable the city planners and inspectors to perform more inspections, do it more accurately, and with less resources in less time, thereby increasing city department efficiency and productivity.

- Increased city resilience (power, communications, information, health). Smart buildings are equipped with a robust power, digital and telecommunications infrastructure. From in-building small cell private and public, land mobile radio (LMR) networks to satellite to wi-fi and IoT connectivity technologies, smart buildings bring a resilient communications infrastructure. Similarly, smart buildings may be equipped with a variety of power generation capabilities (solar, batteries, generators), reducing dependence on external sources, and may act as a microgrid. Smart buildings leverage data, algorithms and its array of sensors to inform, augment and support human responses in critical situations (e.g. location of an incident, wayfinding, etc.). Smart buildings enable its occupants and tenants to continue on-site business operations, and thus ensure physical operational continuity. From a resilient city perspective, smart buildings provide the city with limited communications and operational functionality during unplanned emergencies and incidents.

- More effective community engagement channels. There is no one size fits all channel to reach and engage community members living, working or visiting a city. A smart building, with its advanced digital and communications infrastructure, provides additional mechanisms for engaging the community. Its digital signage systems can be used to provide news, events information, safety alerts, mass notifications, public transportation information, wayfinding, and other critical messaging to tenants, employees and visitors in real time. In addition, the smart building’s digital infrastructure may also deliver personalized content directly to the user through their smart mobile device. The ability of the smart building to engage more directly, as well as provide timely and vital information to the community is a critical city outcome.

- Increased citizen and community accessibility and inclusion. Inclusion and accessibility is an important, top of mind issue with most cities. The ability to digitally connect their citizens of all ages, genders, sociodemographics and cultures is an important outcome for city leaders. Smart buildings can contribute indirectly to inclusion in a number of ways. They may leverage their robust communications capabilities to provide public Wi-Fi in open public spaces. They may indirectly bring in a fiber infrastructure into a nearby neighborhood or community when planning a fiber infrastructure to support the building needs. They may leverage their building and digital infrastructure to host a variety of telecommunications systems for a city that the municipality may not otherwise have.

- Increased city and community vibrancy. Smart buildings attract new businesses, digital workforce talent, and create demand for new opportunities, skills, and jobs. This new and growing economic vitality creates optimism, drives new growth in the surrounding communities, and brings in new supporting businesses, as well as a continuous influx of new residents and businesses to the civic ecosystem.

- Increased capabilities to support new working and learning options. The advanced digital and telecommunications infrastructure in smart buildings support office to office, office to remote (home, field, etc.), and home to home telecommunications. These capabilities enable new working, learning and care arrangements to support a new and existing workforce, student audience, and patient base. It facilitates access to a new workforce resource pool, delivery of services to a wider base of workers, students, patients and customers. In the current COVID-19 pandemic where face to face interactions and travel outside the home is discouraged, these capabilities support a hybrid (local, remote, and work from home) workforce and maintain essential healthcare and education services.

Innovation Benefits

* More effective new city services enabled by smart building platforms (in number of new services, number of data sets, etc.). Smart buildings will leverage its digital and communications infrastructure, as well as the data collected, to create new insights and services that will be invaluable to the city. As one example, the smart building can be host to a variety of sensors. These sensors may monitor weather conditions, vehicle and pedestrian traffic patterns, building conditions, and contribute to the creation of a digital twin of the city. This digital twin can be used by city planners to model and simulate various city initiatives (for example, to see how changing traffic signals may impact accident rates, air quality levels, pedestrian foot traffic and its impact on surrounding businesses). Information from the digital twin can then be used to design a program, where it can be tested and evaluated. There are a myriad of innovative services, too many to list here, that can be developed by using the data collected from inside and outside the smart building.

- New digital innovation ecosystem supporting future innovation and services enabled smart buildings (in # of new businesses). Smart buildings over the next few years require a new supporting ecosystem of services and skills to design, build, support and operate it. Equally important, the smart building is a platform for future innovation, with many of these future services not yet discovered or enabled yet. These future innovations and services, built on top of the existing smart building infrastructure, capabilities and skills, will be even more transformational. These innovations will attract new talent and skills, new businesses and accelerate the expansion of the ecosystem of businesses needed to support smart buildings (and the smart city).

- Smart Buildings as connected intelligent nodes in a city forms a smart mesh network allowing for meta behaviors and communications to form. These capabilities drive synergistic efficiencies and enhanced resiliency of the city. New capabilities include: local coordinating last mile traffic flow management: anticipating bottlenecks and supporting rerouting and time sequencing of arrivals and deliveries; local power generating and demand loading; advanced warning of various disruptions and events - flooding, cyber attacks, civil unrest; and reconfiguration of building facade and structures to form local social spaces for a range of events. Smart building benefits grow exponentially when multiple buildings are connected to the same power grid and backhaul infrastructure to share resources between buildings.

* Enhanced city reputation. Smart buildings enhance the reputation of a city as innovative and forward thinking as it enables the transition of a city into a smart city, one smart building at a time. Smart buildings support lasting economic value by attracting a new ecosystem of tenants and businesses, supporting businesses, as well as new higher paying jobs aligned to the 21st century needs.

As a final step, the initial set of smart building benefits for cities (Figure Eight) is summarized. These benefits are further categorized into the outcome areas that cities care about, and aligned to one or more of the four civic dimensions. The purpose of Figure Eight is to organize the benefits into a format that is directly relevant and consumable by city leaders and others in the ecosystem. Each city may have its idea of strategic, operational, political and emergency/unplanned dimensions. They will reorganize the benefits into these dimensions as needed. This is a necessary step in order to understand, communicate and gain support of city officials for the development (and retrofitting) of smart building

- Black = Direct benefits

- Red = Indirect benefits

- Blue = “Net New” innovation benefits

| Strategic Priorities | Operational Priorities | Political Priorities | Resilience Priorities | |

| Quality of Life |

|

|

|

|

| Government Efficiency |

|

|

|

|

| Health and Wellness |

|

|

|

|

| Economic Development |

|

|

|

|

| Sustainability |

|

|

||

| Public Safety |

|

|

| |

| Mobility | ||||

| Resilience |

|

|

|

First Steps to Consider

- Review and understand the framework. The framework is a structure for aligning the key smart building value and benefits to the issues that cities and communities care about. Adapt the framework, as appropriate, to the needs of your specific situation.

- Understand and document some of the specific outcome categories and priorities of relevance to a city and community. These will differ from city to city, and community to community. Some of this information is available in reviewing the community’s general plan or vision documents (and its corresponding departmental plans). Others may be found in city council meeting minutes, and from conversations with various city operations and political leaders.

- Identify smart building services, capabilities and value that aligns to the specific needs of the community or city. The more of these relevant services or capabilities can be identified and/or created, the more support the smart building will receive from the community. These services and capabilities should be incorporated into the smart building development or retrofit as early in the cycle as possible.

- COVID-19 is currently top of mind with cities, communities, building owners, commercial real estate companies and tenants. Identify smart building services and capabilities, such as those that lead to the creation of “COVID-19 safe spaces”, into the building design and retrofit.

- Think beyond COVID-19 and identify resilience needs that a smart building can address. These may include a variety of natural hazards (earthquakes, hurricanes, etc.), as well as man-made events (acts of terrorism, industrial accidents, civil unrest, etc.). Integrate smart building capabilities and update community resilience and emergency response plans.

Key Walkaway Points

- Cities create civic outcomes for its residents, businesses and visitors. These outcomes fall into eight areas – government efficiency, economic development, health and wellness, mobility, quality of life, resilience, public safety and sustainability.

- Focus on a different set of ROI metrics when evaluating the value of smart buildings to cities. The ROI of smart buildings is different for cities than for building owners, commercial real estate companies and tenants. Cities look beyond financial metrics, and focus on smart buildings contribute to the creation and delivery of civic outcomes.

- The value created for cities by smart building fall into three categories – direct, indirect and innovation. Direct benefits are those benefits that arise as a direct consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service in creating a civic outcome. Indirect benefits are those that arise from a secondary consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service. Indirect benefits are those that arise from a secondary consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service.

- The value and ROI of smart buildings are reviewed against four dimensions that cites care about. There is no one single view of an outcome - different stakeholders within the municipal ecosystem will be looking at the outcomes from one of these perspectives. These dimensions are strategic, operational, political and emergency/unplanned (resilience). The strategic dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with a city’s long term vision and strategic needs. The operational dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with the day-to-day “run the city” activities and how well the city is able to provide services effectively and efficiently. The political dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with the long term and day-to-day electoral, governance and legislative needs of the city. The emergency or unplanned dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits (also known as resilience dividends) are aligned with the resilience capabilities and resource needs of the city when something unexpected occurs.

* A new framework is provided here for cities to evaluate the value of smart buildings. This framework organizes the value provided into the outcome areas that cities care about, and aligned to one or more of the four civic dimensions. The information is presented into a format that is directly relevant and consumable by city leaders and others in the ecosystem.

Closing Thoughts

A smart city is built one street, one neighborhood, one school, one community, one business district, one building, one business park, and one university campus at a time. Smart buildings are important building blocks of a smart city.

Whether you are a municipal official developing policies for smart buildings, or an urban planner developing strategies for smart buildings, or a building developer or investor planning smart buildings, the value and ROI of smart buildings to a city goes beyond the traditional financial metrics used by business enterprises.

The concept of ROI for cities differs from that for businesses. Cities are not in the business of maximizing profit, nor do cost savings get returned to taxpayers. Cities are in the business of delivering outcomes to its constituents in a cost effective, responsive and effective way. Cities are continuously developing and building on these services to deliver services. City services are typically cost centers, and not profit centers. Cities rely on tax revenue, bonds, grants and other financing mechanisms to develop, operate and deliver services. Unlike a business, a city is not in the position of generating profits from its services, but to partially offset costs of maintaining and delivering those in part or in whole. Any profits earned from city services is used to fund existing operations or new initiatives that create desired outcomes.

Because of this, the value and ROI that smart buildings have on cities are different than the ROI that smart buildings have for building owners, tenants and others. In this case, it is necessary to expand our thinking beyond and look at the social, community benefits, or the Return on Community. These are a very different set of lenses.

A framework for thinking about smart building ROI for a city, and provide a structure for identifying, classifying, and ultimately communicating those benefits to stakeholders in a relevant and consumable format is shared here. In the future, as smart buildings emerge in greater numbers and grow in maturity, it is possible to better quantify the social and community benefits of smart buildings.

- ↑ Planning sustainable smart cities with the Smart City Ecosystem Framework, January 24, 2018, https://strategyofthings.io/smart-city-ecosystem

- ↑ Smart buildings – what’s in it for cities (Part One), March 22, 2020, https://strategyofthings.io/smart-buildings-part-one

- ↑ Smart buildings – what’s in it for cities? (Part Two), March 22, 2020, https://strategyofthings.io/smart-buildings-part-two

- ↑ City of Henderson Smart City Strategy, February 18 2018, https://cityofhenderson.com/docs/default-source/information-technology-docs/henderson_smart_city_strategy.pdf?sfvrsn=2