Resilience Hubs

| Buildings | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sectors | Buildings Wellbeing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contact | Stan Curtis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Activities

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Authors

This chapter demonstrates how integrated smart systems that draw on a number of technologies, processes, and data can enable a community structures to function more efficiently for their main purpose as well as be prepared to serve as a “community resiliency hub” and/or “emergency shelter” as needed. Selecting a school as a community resilience hub leverages its existing function for families already charged with protecting children, employing vetted professionals, and communicating with parents, public safety agencies, and city government as well as embuing the school with some additional important functions and responsibilities to an extended community population. (The pilot for this project--using the Buckman School in Portland, Oregon--received a National Science Foundation Planning Grant in 2022.)

- While emergency operations are run by highly skilled professionals in post disaster situation they lack outreach and community engagement in pre Disaster Preparedness Planning. Our objective than is to remedy this situation by designing an appropriate equitable system customizable to particular type disaster and socio-economic conditions of a community. Schools offer the best opportunity for community resilience hubs because their location is well known in the community because:

- They are places where do people instinctively turn to, when the disaster strikes, if only to know their kids are safe.

- Are places where citizens come together, volunteer, build skills, access community programs, become physically active and build strong and healthy communities.

- Pretty much everybody in a community knows where the school is.

- In times of disaster, schools also have much of the infrastructure and capabilities to serve as resilience hubs.

- School have a fleet of buses and drivers who are familiar with community routes.

- Schools have showers and toilets and gyms where people can shelter.

- They usually have a kitchen and cafeteria, sometimes an infirmary.

- There are playgrounds where additional temporary enclosures can be erected and there is a Parking for emergency services.

- There is a historical precedent for schools as civil defence centers and even fall out shelters.

- Suggested measures are grouped into the following categories

- Community Disaster Management and Resilience Planning

- Connectivity,

- Communications and Public Safety

- Site,

- Energy/ Grid Connectivity,

- Water,

- Supplies,

- Indoor Environment

- Community Engagement

- Specific measures are discussed under these respective headings below

- FEMA’s twelve steps are a useful approach in evaluating the needs and risks of setting up the school as a community resilience hub and those to the community for which it serves.

| Areas of Focus / Steps / Key Questions | Responses to ? / Technology Identification | Key GCTC POC or Group Resource | External Contacts to Tap

(Individuals or Organizations |

| A. Risk Evaluation and Community Engagement in the Planning Process (based on FEMA) | Jiri?

|

||

Step 1: Initiation: Scope the Plan& Create a Steering Committee

|

NIST Special Publication 1190:”Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buildings and Infrastructure Systems”, Vol. 1&2 2016

|

|

|

Step 2: Create a vision statement for a how this project can help to enable / strengthen a community to be a Smart, Connected, Safe and Sustainable community

|

|

||

Step 3: What are the key hazards this community has or may face (prioritize by risk level: potential to occur and resulting impact on lives and property) and where are the current assets that will be used to address these threats? Where assets are, and where hazards occur, and evaluate the risks

|

|||

Step 4 : Identify current disaster mitigation action plans and residual risk

|

|

||

Step 5: Identify prioritized disaster response goals, objectives, targets and indicators for each different stakeholder group in the community?

|

|||

Step 6: Conduct a Sustainable Community baseline assessment

|

|

||

Step 7: Identify Safe Community goals, objectives, targets and indicators

|

|

Nowcasting the Next Hour of Rain | |

Step 8: Brainstorm potential Smart, Connected, Safe and Sustainable actions

|

|||

Step 9: Evaluate each proposed action

|

|||

Step 10: Select actions

|

|||

Step 11: Write the Plan

|

|||

Step 12: Evaluate the Planning Process

|

|||

Early Warning System (EWS) for Threats and approaching Disaster

|

FEMA: The National Risk and Capability Assessment (NRCA) https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/risk-capability-assessment

|

||

B. Connectivity, Communication, and Security / Resilience Network with levels of government, other communities and facilities.

|

Ann, LAN, Debbie | Potential RENS / Public sector connectivity orgs: e.g., Link Oregon (OR), CENIC (CA), PNWGP (WA), et al. | |

|

Cisco Network Emergency Response Vehicle (NERV) https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/en_us/solutions/industries/docs/gov/NERV_AAG.pdf

https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/about/csr/impact/critical-human-needs/tactical-operations-tacops.html

|

||

C. Energy/Grid Connectivity

A high performance (working) school building is proposed with a high quality building Roof, walls and windows of the schoolWhat does "envelope" mean in this context?envelope as well as high efficiency mechanical and lighting systems. |

Stan? | ||

Specific measures include:

|

Battery storage can be mobile in form of electrical school

PORTLAND (PGE) HERE: is our Portland General Electric (PGE) support for school buses (battery-storage) https://portlandgeneral.com/energy-choices/electric-vehicles-charging/pge-electric-school-bus-fund

SanDiego Gas &Electric (SDGE, Sempra) also has leading microgrid programs including school-solar & bus/fleet charging - Nuvve has a popular Bus-Fleet charging (bi-directional) capability.

http://www.greenschools.net/article.php-id=148.html https://www.kpbs.org/news/2020/sep/15/solar-power-shines-california-schools/

Portland General (PGE) and Connected Communities grant - Neighborhood Power, community grid program - Portland Public Schools (PPS) "Project Zero" education program - PGE Electric School Bus Fund - Beaverton Community Resilience Center ...Public Safety program

|

SAN DIEGO (Nuvve bidirectional charging)

SanDiego Gas &Electric (SDGE, Sempra) also has leading microgrid programs including school-solar & bus/fleet charging - Nuvve has a popular Bus-Fleet charging (bi-directional) capability. https://nuvve.com/nuvve-activates-bidirectional-flow-of-energy-from-electric-school-buses-to-con-edisons-grid/

http://www.greenschools.net/article.php-id=148.html https://www.kpbs.org/news/2020/sep/15/solar-power-shines-california-schools/

| |

| D. Water

|

|||

Specific measures include:

|

|||

E. Site

|

|||

A compact development footprint is proposed, Specific measures include:

|

|||

F. Resources and Physical design

|

|||

Specific measures include:

|

|

||

| G. Indoor Environment | Phyllis/ Manfred?

|

||

A very high quality indoor environment with high air ventilation rates and IAQ monitoring. Specific measures include:

|

|||

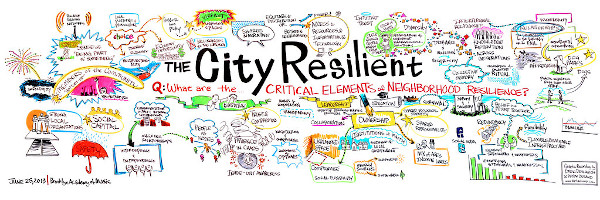

| H. Community Engagement and Operations. | Deborah? | ||

|

Virginia Smart Community Testbed

|

||

I. Equity

|

|||

|

|||

| J. Funding options | |||

| Federal

State Regional Local Community-based |

Federal

|

||

| K. Other Considerations | |||

Reference Materials

FEMA Community Lifelines Implementation Toolkit

WSDOT Kingsgate Park and Ride Transit Oriented Development Pilot

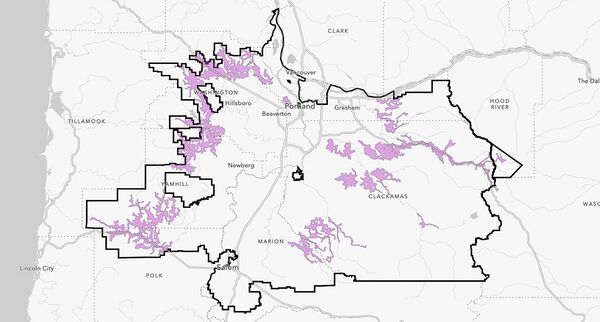

- PGE Power Safety Power Shutoff Map

The light purple areas show the zones in our service territory that are currently at a higher risk for a safety-related outage. Click on an area in the live map or enter your address in the box to pinpoint your location. This map will update throughout the wildfire season with additional details and information.

Demonstration Projects

|

CIVIC school HUBS | |

| NSF CIVIC grant to incubate the Federal School Infrastructure Toolkit for more resilience Community services. A pilot program with be developed with the BENSON school district in Portland, and woven into the urban/rural network of the Metro regional emergency response. | ||

|

Resilience HUB - East Multnomah | |

| Resilience Hubs are community-serving facilities augmented to support residents and coordinate resource distribution and services before, during, or after a natural hazard event. They leverage established, trusted, and community-managed facilities that are used year-round as neighborhood centers for community-building activities. Resilience Hubs can equitably enhance community resilience while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improving local quality of life for our communities. They have the potential to reduce burden on local emergency response teams, improve access to public health initiatives, increase the effectiveness of community-centered institutions and programs. | ||

|

Resilience HUB - NIST Guide | |

| Natural, technological, and human-caused hazards take a high toll on communities, but the costs in lives, livelihoods and quality of life can be reduced by better managing disaster risks. Planning and implementing prioritized measures can strengthen resilience and improve a community's abilities to continue or restore vital services in a more timely way, and to build back better after damaging events. That makes them better prepared for future events and more attractive to businesses and residents alike. | ||

|

Resilience HUB - Vibrant Hawaii | |

| A goal of the Resilience Hub initiative is to build individual capacity and community networks to be resilient and ready for anything. To get there, Vibrant Hawai'i hosted a Resilience Leadership Academy (RLA) - a monthly development program with curated content by local experts. | ||

Reports

|

Guide to Developing Resilience Hubs | |

| Climate change is happening now. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the number of billion-dollar disasters has risen significantly over the last ten years. As the ten warmest years ever recorded have happened since 1998, so have the costliest weatherrelated disaster events. As the globe continues to warm, extreme weather events will continue to threaten and impact communities, infrastructure, and systems worldwide. | ||

|

Shifting Power to Communities and Increasing Community Capacity | |

| In all U.S. cities, massive disparities exist between people and neighborhoods. Communities of color and lower income communities sufer disproportionate impacts of climate change and yet are often the last communities supported in the event of an emergency. These communities also generally have less access to resources to respond and recover. Achieving community resilience requires equitably supporting all members of the community, and prioritizing those who experience greater risk to their homes, their jobs, their communities, and their health. | ||