Public Safety

- Authors

Public safety refers to the measures taken to protect the public from harm and maintain order in a community. Overall, the goal of public safety is to ensure that the community is safe and secure for everyone, and that individuals and families have the support and resources they need to stay safe and healthy.

This can include a wide range of activities, such as:

Providing emergency services, such as firefighting, paramedics, and emergency medical services

Preparing for and responding to natural disasters and other emergencies

This Blueprint is organized around the following four Focus Areas1 under the scope of public safety:

- Emergency Services: Coordination of emergency operations among responder agencies (i.e. firefighting, medical, emergency management, search and rescue, and law enforcement)

- Law and Order: through activities like policing and community policing

- Emergency Preparedness: Coordination of local, state, and federal resources across the emergency management cycle (Prevention, Protection, Mitigation, Response, Recovery)

- Disaster Recovery: Restoration and integration of economic, social, policy, communications, and governance functions during post-disaster community recovery

- Business Continuity: The processes and procedures an organization puts in place to ensure that critical business functions can continue during and after an unexpected disruption, such as a natural disaster, cyber attack, or power outage.

- City Resilience: Application of advanced technologies to the broader challenges of community resilience, environmental and public health, quality of life, and social cohesiveness and identity.

- Educating the public: about safety issues and how to protect themselves and their property

- Providing services and support: to victims of crime and abuse

Each section addresses specific requirements that determine the approach for technology research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E), as well as technology applications and systems relevant to the individual Focus Areas. These contribute to the goal of smart public safety implementation addressed in Section V. Finally, the last section addresses next steps for communities and for the Public Safety SuperCluster, itself. The Blueprint is therefore intended to also serve as the charter for an ongoing public-private partnership (PPP) to bring together member communities, technology developers, research laboratories, and end-users to identify challenges and define requirements for public safety in S&CC and share best practices, concepts of operations, and form pilot studies for technology test and evaluation. Annex 1 addresses specific considerations of Cybersecurity and Privacy in the context of public safety.

Background and History of the Public Safety Initiative

The initiative for Smart Public Safety in Connected Communities is a collaboration among city -based technology development teams dedicated to addressing current and future chal lenges in public safety within S&CC. This initiative originated from the NIST-sponsored Global City Teams Challenge. Established in 2014, GCTC serves as a platform for local government agencies and technology providers to identify solutions to vexing municipal problems through the deployment of smart city technology applications. The GCTC is comprised of geographically focused “Action Clusters” from cities across the U.S. and the world. Its goal is to spur collaboration among innovative local governments and agencies, nonprofits, and private companies to overcome challenges and develop solutions with leaders in the Smart City and Internet of Things (IoT) fields. Through participation in the GCTC, companies, universities, and nonprofits showcase their technologies to potential customers or partners and collaborate with local government leaders and technology developers to deploy interconnected solutions, thus contributing to NIST’s effort to develop technical standards for IoT and S&CC.

In October 2016, the GCTC organized Action Clusters into a set of “SuperClusters” based on specific community services and mission areas. The Public Safety SuperCluster (PSSC) was formed with the goal of identifying technologies, processes, and strategies from among GCTC members to enhance public safety, emergency preparedness and management, disaster recovery, and community resilience. The PSSC’s initial goals were to:

- Develop, integrate, and pilot technology applications, and test new operational concepts and employment methods in collaboration with first responders, public safety officials and government agencies; and

- Improve disaster preparedness, response and recovery and improve overall community resilience against the hazards and risks that threaten modern societies.

In addition, the PSSC aims to improve policies and procedures for integrating advanced communications methods and decision systems to enhance interagency planning, situational awareness, and coordination of resources within S&CC. The PSSC focused specific attention on the integration of current and future technologies (cloud computing, big data analytics, mobile connectivity and social networking), as well as innovation accelerators required to deliver outcomes (e.g., Internet of Things ( IoT) and cognitive technologies) required to digitally transform public safety, and to build resilience and sustainability into the technology ecosystem that comprises S&CC.

Currently, few formal venues or opportunities exist for collaboration between technology researchers and developers, public safety agencies and professionals, and local government officials and community leaders where capability gaps and priorities for public safety, resilience , and sustainability can be discussed and potential technology solutions identified. Moreover, the trend toward S&CC—coupled with dramatic change in hazards and threats to complex, urban societies—argues for a standing organization and framework for identifying innovative public safety technologies, strategies, and capabilities within a fully collaborative, multi-disciplinary environment. To that end, this initiative aims to form an enduring Public-Private Partnership to build capacity in interdisciplinary, integrative research in public safety technologies across a coalition of public safety officials, private sector developers, university researchers, community stakeholders, and government agencies to examine innovative concepts that enhance public safety, community resilience, and urban sustainability. The initiative has four objectives:

- Identify capability gaps and national challenges in public safety that existing and maturing research projects among GCTC member communities and technology firms can address;

- Establish a forum for nurturing integrated, multi-disciplinary research in public safety strategies and technologies with input from first responders, emergency planners, and community leaders;

- Identify opportunities to collaborate with state, county, and municipal partners to define requirements and validate approaches for enhancing community resilience and responding to and recovering from disasters and civil emergencies; and

- Identify opportunities for supporting programs in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) education to engage students and emerging scientists and professionals and nurture the next generation of researchers, technologists, and practitioners dedicated to research and technology development in the interest of public safety.

The immediate goal is to increase awareness of emerging technology applications and enhance opportunities for collaboration among GCTC member communities and S&CC partners in the areas of public safety, security, and resilience. More broadly, this initiative serves as a dedicated forum for information sharing to advance state-of-the-art, public safety-related technologies and concepts. The initiative will encompass technological, social, and security dimensions of public safety enhancements and determine requirements for both cognitive and collaborative infrastructures, broaden awareness and expand knowledge of technology developments, and disseminate outcomes through GCTC, S&CC, and the public safety community. It will serve as a repository of current best practices in Smart Public Safety, and support the expansion of this concept to other communities in the U.S. and internationally.

A “Whole Community” Approach to Public Safety

The starting point for Smart Public Safety in S&CC is recognition that emergency preparedness, response, and recovery is a “whole-of-community” responsibility that integrates resources, capabilities, technologies, talent and leadership from across government and public sector agencies, first responders and emergency management, privately held utilities and services, commercial entities, local leadership, and residents. Traditionally, public safety has been the domain of trained professionals―including law enforcement officials, first responders, emergency management agencies, and critical infrastructure providers and operators, such as electrical power companies and public works and transportation agencies. Planning, training, exercising, and preparedness has fallen on those agencies as part of their professional preparation for incident response. In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) developed formal doctrine for emergency and disaster response under an Incident Command System (ICS) and then incorporated this into the National Incident Management System (NIMS) to standardize emergency operations and establish a framework for coordination among responders, units, and jurisdictions and support mutual assistance.

Coordination with the civil population, however, had been largely confined to exercises involving segments of local government agencies and leadership, and the occasional table -top or scenario-based exercise involving support from local community groups—usually in the role of victims or casualties for the benefit of training professional first responders, emergency managers and elected officials.

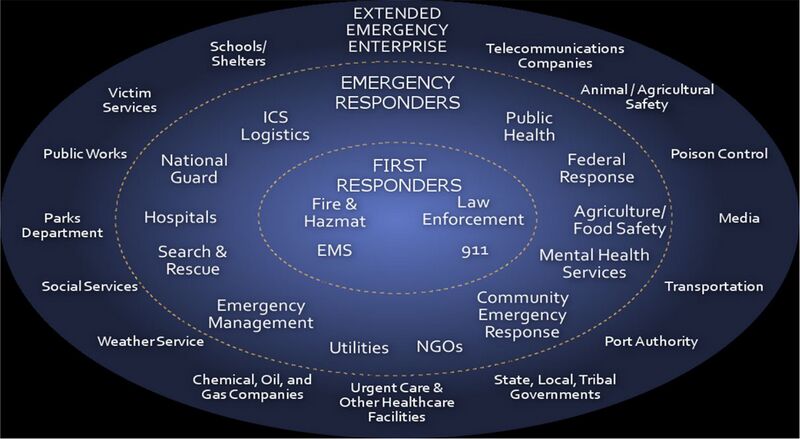

More recently, it has been widely acknowledged that disaster response, as well as pre-paredness and recovery, involves the entire civil population of a community. This has led to the emergence of the whole-of-community strategy for disaster and emergency management and publication by FEMA and U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) of the National Preparedness Goal (2015), the National Mitigation Framework (2016), and the National Disaster Recovery Framework (2016) that emphasize whole community responsibility for disaster planning, preparedness, and response. This perspective of the collective responsibility is not limited to disaster and emergency management agencies, but is also seen in the U.S. Department of Justice Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program, which engages the public through community outreach, engagement, and education to improve community security and safety and to improve police-community relations. Figure 1 shows a federal view of the roles and resources that the whole of community approach to public safety can engage.

Envisioning a Smart Public Safety Ecosystem

A significant aspect of the Smart Public Safety Initiative is its charter and composition as a PPP dedicated to requirements definition and technology development across the entire public safety sector—not simply for coordinating disaster response and recovery operations. In relation to the whole-of-community approach to disaster management, the concept of the PPP has come to mean the formalization of the need to share information and resources between public sector agencies and private sector businesses and non-profits as a “force multiplier” for local or regional disaster preparedness, prevention, response and recovery. In the context of Smart Public Safety, however, the PPP ’s role also includes identifying challenges and requirements and applying new technologies that are jointly designed, developed, prototyped, and fielded by a partnership of technology firms, research centers (including university, commercial, and government affiliated centers), government agencies, first responder groups, and public service end-users.

In the daily management of Public Safety Incidents, a wide range of personnel, agencies, and resources is often involved in the response to a critical incident. Figure 2 shows the numerous resources, agencies, and participants responsible for implementing community-wide Smart Public Safety. The center represents the primary First Responder community (law enforcement, fire/search & rescue/hazmat and EMS) and 9-1-1 call-taker/dispatch centers. Surrounding these first responder agencies, lead and supporting agencies provide specific technical capabilities and services during an incident. At the outer- most ring, extended emergency enterprise organizations may have supporting roles and responsibilities at times during incident management.

A fundamental principle for technology development in the public safety arena is the value of dual-use or multi-purpose technology applications that public safety can leverage both during normal operations (“Blue-Sky Days”), as well as during emergency or disaster situations (“Dark-Sky Days”). This approach to smart public safety is cost-effective and facilitates efficient operations because users are already familiar with systems from daily use that they will apply during a crisis.

The capabilities expected of the Smart Public Safety program touch upon three key areas:

- Improved safety and situational awareness for first responders, incident command, local authorities, and governance (to include community leadership);

- Enhanced collaboration between agencies to enable the whole-of-community approach to planning, preparedness, response, and recovery; and

- Mission-effectiveness, defined as the efficient employment of resources involving all responsible agencies or organizations across the full spectrum of emergency or disaster management.

Defining PSSC Focus Areas and Scope

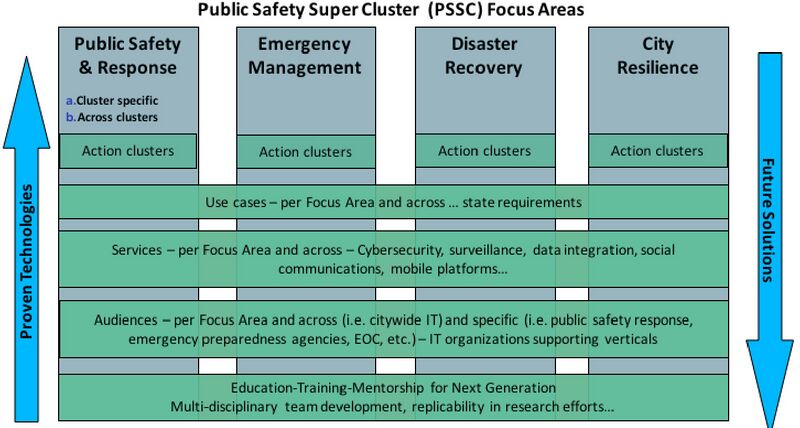

In March 2017, the PSSC conducted a series of online surveys and held a two-day workshop among its member communities to determine the PSSC scope and focus. Participants identified four Focus Areas (Public Services, Emergency Management, Disaster Recovery, and City Resilience), each with distinct characteristics and specific technology requirements, yet also sharing elements such as use cases, services, users, and education and training opportunities (Figure 3). The exercise enabled PSSC Action Clusters to identify an “entry point” for individual technology applications either developed or in development to solve specific local problems in public safety. Collaboration among PS SC member communities also helped identify opportunities to apply individual technologies across focus areas.

The diagram’s structure served as the process guide for PSSC Action Clusters to design and organize an approach to Smart Public Safety that evolved into this Blueprint. Elements of the process included:

- Participation of GCTC Actions Clusters that formed the original membership of the PSSC, along with their individual, city-based technology solutions;

- Development of a series of use cases, incident scenarios, and technology requirements that served as frames of reference or context for the PSSC Action Clusters (see Appendix C);

- Identification of the emergency and community services that apply across each Focus Area;

- Stakeholder input from audiences, agencies, and participating actors involved in community Public Safety;

- Recognition of the need for education, training, and mentoring initiatives that are directed toward Smart Public Safety.

The two arrows on either side of the diagram indicate that the PSSC Blueprint is based on existing proven technologies for public safety, as well as those that define or will address future needs, requirements, or solutions. In the March 2017 PSSC workshop, each Focus Area team was given a 2-part task:

- Define the Focus Area Scope Statement, Mission Statement, and Focus Area goals; and

- Identify departments within public safety agencies, components of those departments, significant city requirements, and existing resources to meet those goals.

Teams then described best practices and guidelines that city agencies can use to plan for and implement a “Smart Public Safety” program within a specific region, community or jurisdiction.

As an example, some capability gaps described in this blueprint are associated with the inability of agencies or organizations to access broadband services and gain critical situational awareness during emergencies. Lack of interoperability between f irst responders is a fundamental capability gap , and is often a consequence of inadequate access to the technology that enables mission critical interoperable broadband communications, in-field sensor-based data capture, real-time data analytics to analyze said data, and visualization solutions that most expeditiously provide that information back out to incident command and affected stakeholder groups. The lack of timely and sufficient incident data—or the ability to transmit and receive that data—is a capability gap that contributes to suboptimal situational awareness at the Incident Command Post or Emergency Operations Center (EOC ). Major capability gaps during emergencies can often be traced to a common issue: inadequate access to applications, shareable information, and timely actionable intelligence due to the lack of a dedicated high-speed data network to make the information accessible. Smart Public Safety solutions that address the needs for new or advanced technologies, agency policies or enhanced Standard Operating Procedures , and integrated training between personnel involved in the activities of the four Focus Areas identified by the PSSC can play a key role in resolving these gaps.

Cybersecurity and Privacy

In 2018, the GCTC began integrating Cybersecurity and Privacy into the S&CC program with the establishment of the Cybersecurity and Privacy Advisory Committee (CPAC) and designation of the Secure Communities and Cities Challenge (SC3) as the next phase of the GCTC. In Fall 2018, the PSSC conducted a workshop focused on identifying aspects of Cybersecurity and Privacy to be incorporated into the overall Public Safety program. This update to the Blueprint for Public Safety in Smart & Connected Communities reflects the broadened scope of the PSSC and the work of the CPAC in developing a Guidebook for Cybersecurity and Privacy.

Smart city public safety refers to the use of technology to enhance and improve public safety in a city. This includes the use of sensors, cameras, and other forms of data collection to gather information about potential safety hazards, as well as the use of advanced analytics to make sense of that data and inform decisions about how to respond. Some examples of smart city public safety applications include:

- Surveillance cameras that can automatically detect and alert authorities to suspicious activity

- Intelligent traffic management systems that can help reduce congestion and improve emergency response times

- Predictive policing models that can help identify areas at high risk of crime and allocate resources accordingly

- Emergency management systems that can automatically notify first responders and the public about potential hazards, such as severe weather.

By using technology to gather and analyze data in real-time, smart city public safety aims to make cities safer, more efficient and more responsive to the needs of citizens.